Peter's Nite

Peter's NiteRoast Chicken, Potatoes, Tomatos, Ice Cream, Apple Torte

Disinfo on Cronenberg: If there is a filmmaker who has accurately captured the pathological undercurrents of late 20th Century terminal life: institutionalised disaster areas, deviant sexual impulses spinning out of control and the rise of a Dark Culture, it is truly Canadian David Cronenberg.

Cronenberg established a strong following with his early theatrical films Shivers (1975), Rabid (1976) and The Brood (1979). Like Dario Argento, George A. Romero, John Carpenter and David Lynch, Cronenberg has used familiar 'visceral horror' film motifs like urban alienation and body mutation to reach art-house audiences. But he has never seen himself as a strictly horor director, and has viewed his films as highly personal meditations. Cronenberg's influence is often unacknowledged: for example, elements of his early films clearly inspired parts of Ridley Scott's Alien (1979).It was the pre-cog mutant hero of Scanners (1980) which really signalled that Cronenberg was daring to intelligently explore realms that others left unventured. Cronenberg used 1950s pulp SF themes in a thinly veiled allegory hinting at the Thalidomide tragedies and contemporary pharmaceutical experimentation. Videodrome (1981) upped oft-quoted Canadian theorist Marshall McLuhan's media theories by literally exploring the New Flesh. Panned on release, Videodrome presciently captured the underground interest in body scarification/modification and pirate cable TV long before cyberculture became fashionable, and is regularly cited by film aficionados. Its mediation on the body/technology dichotomy hinted at coming 'meatspace' flashpoints like Heaven's Gate.

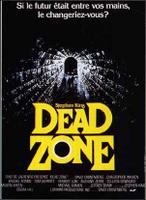

Much of Cronenberg's 1980s output occupied the twilight-zone between art-house auteur and mainstream cross-over. His version of Stephen King's Dead Zone (1983) re-shaped a rambling story into a Reagan-era apocalyptic mindscape, while The Fly (1986) foreshadowed the Human Genome Project in its controversial depiction of human sexuality. Dead Ringers (1988) is regarded by many as Cronenberg's finest project to date: a subtle and unsettling psychological exploration of cojoint twins and identity swapping. For Night Breed (1990), Cronenberg teamed up with acclaimed horror author Clive Barker to explore a society of shape-shifting misfits. The ironic twist was that Barker wrote and directed the film, and Cronenberg starred as the nefarious Dr. Philip Decker.Controversy surrounds Cronenberg's adaption of William S. Burroughs' Naked Lunch (1991), as Cronenberg mixed biographical elements with an exploration of Interzone. Some purists felt that the film was confusing, and that the original cut-up novel was unfilmable. However others felt that Cronenberg was the best director for the job. M. Butterfly (1993) and Blood and Donuts (1995) both received mixed reviews, as some critics felt that Cronenberg was trying too hard to achieve mainstream success.

But no reservations could be made about Crash (1996), a stunning adaption of J.G. Ballard's controversial 1973 novel that explored auto-crash fetishes, deviant sexuality and the rise of the automobile as an arbiter of the contemporary psyche. New Line Cinema owner Ted Turner found the film so controversial that he shelved it for months. After dominating the Cannes Film Festival (where it was awarded the Special Jury Prize), Crash received strong worldwide reviews and pro-active support from Ballard.

With eXistenZ (1999), Cronenberg returned to writing and directing, creating an unusual exploration of bio-engineered video-games that was decidedly different from The Matrix (1999) and other virtual reality thrillers. The pro-life extremists became suddenly very real during the video-game/violence debates after the Littleton and Columbine shootings.

Having established himself as a formidable force, David Cronenberg continues an independent course into the twilight visions of his own atavistic primal mindscape.Controlling the audience: Even Hitchcock liked to think of himself as a puppeteer who was manipulating the strings of his audience and making them jump. He liked to think he had that kind of control. I don't think that kind of control is possible beyond a very obvious kind of physical twitch when something jumps out of the corner of a frame. I also think the relationship I have with my audience is a lot more complex than what Hitchcock seemed to want his to be -- although I think he had more going on under the surface as well.

But you can't control all of that. Anybody who comes to the cinema is bringing they're whole sexual history, their literary history, their movie literacy, their culture, their language, their religion, whatever they've got. I can't possibly manipulate all of that, nor do I want to. I'm often surprised -- I expect to be surprised -- by my audience's reactions to things.

Adaptation: Asked if it requires extra effort to leave his own imprint on an adaptation rather than an original script, Cronenberg says, "I know that it's going to be my film, because I'm going to be making 2,000 decisions a day while we're making it, and no one else would make those same 2,000 decisions. I will mix my blood with it, and it'll be enough to satisfy me."On Storyboarding: I never storyboard, there's not that kind of intentionality. It's not a religious thing with me, but I really have disdain for storyboards. I know that because of Hitchcock and his own mythology, which was a lie and a product of his egomania--and I haven't seen Road to Perdition but I understand Sam Mendes, it's only his second movie and he storyboarded each of his scenes...

But that cuts out the acting, you know, it cuts out a lot of collaborators. I don't want to set it up so this scene has to be set up against the window and the rain, because what if the actor has a great idea for a movement away from the window to the piano? You lock that possibility out when you storyboard and I never want to shackle myself that way. I want to feel it--to move the actors around the room and look at it. Having said that, I do send Peter and Howard and my editor Ron Sanders and [production designer] Andrew Sanders, those are the first people I send a script to and I do it really early on when I'm seriously thinking that it's a movie I want to do, because I want them to start thinking about it even when they're all over the world doing other things. I want them to think about the casting, even. Peter and I, we both work very intuitively. We often talk about coming up with a look, but basically we just start.Horror as a freeing genre: Yes, in a way, you're protected by the genre, because people's expectations are different. Their understanding and approach to what they're watching is quite different when they know they're watching a horror or sci-fi film. Material that would be very difficult to do -- to finance and get an audience for -- if it were just a mainstream, straight, realistic drama is very doable within the protective confines of horror. And I use The Fly, your favorite film [Laughs.], as an example. If you look at it just as a drama, it's about two very attractive, eccentric people who meet and fall in love. One of them contracts a hideous wasting disease and his lover watches helplessly until she helps him commit suicide. That's basically the plot of The Fly when it's stripped of its horror/sci-fi elements. That's a very tough sell! It would be a very hard movie to watch, emotionally and so on, but because of the other things that are going on in it, you can tell that story with all the emotion you want, but it's still somehow absorbable. There's a sort of distancing effect. There's a fantasy element. And it's always very interesting to me that people who love The Fly, often, it's because of the love story and not because of the mechanics of it. It obviously touches people, but it's bearable. That would be a very tough story to sell in a realistic way. So, within a genre, you can experiment with fantasy, reality and emotion in a way that perhaps would be difficult or impossible to do outside the genre.

Cronenberg on Religion: Q: Most of your films deal with various characters' personal spirituality, yet you have never dealt directly with religion.

Cronenberg: The reason why is that I'm not interested. You're absolutely right. For me, it's not even worth discussion. It doesn't interest me. It interests me only to be discarded. If I start there, I'm mired in a discussion that is very unfruitful to me. I'm simply a non-believer and have been forever. To discuss religion is to put me in a debate with myself. I'm interested in saying, "Let us discuss the existential question. We are all going to die, that is the end of all consciousness. There is no afterlife. There is no God. Now what do we do." That's the point where it starts getting interesting to me. If I have to go back and say, "What if there is a God?" then I'm doing a debate that is not very interesting. You have to create one character who believes and another that doesn't. It's not an issue.

Q. How were you raised?

Cronenberg: I'm an atheist and my parents were both atheists so it was never a big issue, and if I wanted to become an Orthodox Jew, it was never, "You must not do that." And I certainly went through all those things as a kid wondering about the existence of God or not, but at a very early age, I decided we made it up because we were afraid and it was one way to make things palatable.

Stephen King bio: Stephen Edwin King was born in Portland, Maine in 1947, the second son of Donald and Nellie Ruth Pillsbury King. After his parents separated when Stephen was a toddler, he and his older brother, David, were raised by his mother. Parts of his childhood were spent in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where his father's family was at the time, and in Stratford, Connecticut. When Stephen was eleven, his mother brought her children back to Durham, Maine, for good. Her parents, Guy and Nellie Pillsbury, had become incapacitated with old age, and Ruth King was persuaded by her sisters to take over the physical care of the elderly couple. Other family members provided a small house in Durham and financial support. After Stephen's grandparents passed away, Mrs. King found work in the kitchens of Pineland, a nearby residential facility for the mentally challenged.

Stephen attended the grammar school in Durham and then Lisbon Falls High School, graduating in 1966. From his sophomore year at the University of Maine at Orono, he wrote a weekly column for the school newspaper, THE MAINE CAMPUS. He was also active in student politics, serving as a member of the Student Senate. He came to support the anti-war movement on the Orono campus, arriving at his stance from a conservative view that the war in Vietnam was unconstitutional. He graduated from the University of Maine at Orono in 1970, with a B.A. in English and qualified to teach on the high school level. A draft board examination immediately post-graduation found him 4-F on grounds of high blood pressure, limited vision, flat feet, and punctured eardrums.

He and Tabitha Spruce married in January of 1971. He met Tabitha in the stacks of the Fogler Library at the University of Maine at Orono, where they both worked as students. As Stephen was unable to find placement as a teacher immediately, the Kings lived on his earnings as a laborer at an industrial laundry, and her student loan and savings, with an occasional boost from a short story sale to men's magazines.

Stephen made his first professional short story sale ("The Glass Floor") to Startling Mystery Stories in 1967. Throughout the early years of his marriage, he continued to sell stories to men's magazines. Many of these were later gathered into the Night Shift collection or appeared in other anthologies.In the fall of 1971, Stephen began teaching high school English classes at Hampden Academy, the public high school in Hampden, Maine. Writing in the evenings and on the weekends, he continued to produce short stories and to work on novels.

In the spring of 1973, Doubleday accepted the novel Carrie for publication. On Mother's Day of that year, Stephen learned from his new editor at Doubleday, Bill Thompson, that a major paperback sale would provide him with the means to leave teaching and write full-time.

At the end of the summer of 1973, the Kings moved their growing family to southern Maine because of Stephen's mother's failing health. Renting a summer home on Sebago Lake in North Windham for the winter, Stephen wrote his next-published novel, originally titled Second Coming and then Jerusalem's Lot, before it became 'Salem's Lot, in a small room in the garage. During this period, Stephen's mother died of cancer, at the age of 59.Carrie was published in the spring of 1974. That same fall, the Kings left Maine for Boulder, Colorado. They lived there for a little less than a year, during which Stephen wrote The Shining, set in Colorado. Returning to Maine in the summer of 1975, the Kings purchased a home in the Lakes Region of western Maine. At that house, Stephen finished writing The Stand, much of which also is set in Boulder. The Dead Zone was also written in Bridgton.

King on self-doubt: I had a period where I thought I might not be good enough to publish. I started to sell short fiction to men's magazines while I was in college. I got married six or seven months after graduating, and for two years I sold maybe six stories a year, and I had the money I was making teaching, too, and it was a decent income. And then I sort of got out of the Zone. And for a year or so, I couldn't sell anything, and I was drinking a lot, wasn't drugging, couldn't afford it, and I was writing mostly shit, and then Carrie came along and I was OK again. But during that one year, I just thought I'm going to be a high school teacher, and nothing's ever going to happen to me.

Christopher Walken bio: Born Ronald Walken in 1943 in Queens, New York, he studied dancing originally, and his early career included such odd jobs as lion taming. He was influenced to embark on a career in show business by Jerry Lewis. The young Walken was an extra on a show where Lewis and Martin were guest hosts. His early work was almost exclusively on the small screen in TV shows such as "Naked City" (credited as Ronnie Walken), "Hawaii Five-O" and "Kojak".

He made his big screen debut in the 1968 film "Me and My Brother". Other roles in various minor films followed, but it was not until his role as Diane Keaton's slightly psychotic brother in "Annie Hall" (1977) that people really began to pay attention. Although his part was little more than a cameo, his memorable speech to Woody Allen about how he sometimes feels like driving head on into the lights of an oncoming car provided the template for many of Walken's subsequent roles - scary and humorous combined. Walken is also famous for a role he did not get that same year - he was George Lucas's second choice for the role of Han Solo after Harrison Ford. This was memorably spoofed on a "Saturday Night Live" episode years later, where Kevin Spacey played Walken auditioning for the role with his infamous delivery style.

1983 was an important year for Walken as it saw him in two leading man roles where he played somewhat against type for a change. The first of these, "Brainstorm", was a sci-fi thriller about scientists who experiment with recording people's thoughts and was directed by Douglas Trumbull, the special effects genius behind "2001: A Space Odyssey". However, it is mainly notorious for being the last film to star Natalie Wood, who died before principal photography was completed in 1981. She was on a sailing trip with her husband, Robert Wagner, and Walken himself when she drowned. The mysterious nature of her death, and the need to shoot further scenes without her, delayed the release of the film by two years. When it finally did reach movie theaters, the reaction was less than ecstatic.

Walken's other film that year, "The Dead Zone", was far more successful. A fairly faithful adaptation of the novel by Stephen King, it featured Walken in a rare heroic role as schoolteacher Johnny Smith, who receives the gift (or curse) of foresight after awaking from a long coma. Walken's haunted, sensitive performance was a revelation, and made the story possibly even more emotionally powerful than it had been in the novel. The heartfelt character development in the film was also a departure for director David Cronenberg after the extreme nature of his early horror films. One amusing coincidence: early on in the film Walken tells his class he'll be reading them The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Of course, 16 years later, Walken played the legendary horseman himself.More Cow Bell: During a popular Saturday Night Live sketch [1], Christopher Walken played "famous" music producer Bruce Dickinson (not to be confused with the Iron Maiden vocalist), insisting that "more cowbell" is the key to making Blue Öyster Cult's "(Don't Fear) The Reaper" a success: "Guess what? I got a fever. And the only prescription... is more cowbell!" This 2000 SNL skit ends with the words on screen: "In Memorium: Gene Frenkle: 1950-2000". (Frenkle, played by Will Ferrell, was the mythical band member who played cowbell on the track.) The skit may have been influenced by a 1976 SNL moment when Chevy Chase in a long scarf substituted for an absent Mick Jagger by playing the cowbell on musical guest Carly Simon's "You're So Vain."

Walken Interview: Q: One of the things that's distinctive about your work is that the words often come out in a surprising way. Are you surprised too, as you speak them?

A: Yes. One of an actor's most valuable qualities is the ability to surprise the audience, and I'm convinced that in order to do that you have to be able to do it to yourself.

Q: How did you approach 'The Dead Zone'?

In that part I felt really natural, really. I behaved and looked and spoke pretty much like myself. The only thing that wasn't like me was his situation. In a case like that I have to just say to myself, what would it be like if this was your life?

Q: You've played quite a few characters who are traumatized. Is that sense of trauma hard to work for?

A; No. I have a natural kind of foreignness-very hard for me to play a regular guy. There always seems to be something peculiar about him. And I think that has to do less with me-as a person I'm very conservative and predictable: I've been married for 25 years, I pay my bills, I have a very conservative, disciplined life. But whatever quality that is the reason that I am offered jobs, I think that has to do with the fact that I grew up in show business. I was a child performer with my brothers-I wouldn't say "actor," I'm still not sure I can call myself an actor, but I am a performer and I have been since I was 3 years old, one way or another. My brothers and I were models when we were babies. I did musicals until I was 25. I went to a school for professional children, all the people I knew were in show business, I simply grew up in show business in the Fifties in New York when television was born and it was all live, 90 television shows coming out of New York every week, live-Dramas, everything. Howdy Doody.

No comments:

Post a Comment