Peter's Nite

Peter's NiteSalad, Pizza, Brownie Bites (all CostCo meal)

Peter brittle and freaking out.

JB Bird on Paddy Chayefsky (via Museum of Broadcasting)

Sydney "Paddy" Chayefsky was one of the most renown dramatists to emerge from the "golden age" of American television. His intimate, realistic scripts helped shape the naturalistic style of television drama in the 1950s. After leaving television, Chayefsky succeeded as a playwright and novelist. He won greatest acclaim as a Hollywood screenwriter, receiving Academy Awards for three scripts, including Marty (1955), based on his own television drama, and Network (1976), his scathing satire of the television industry.

Chayefsky began his television career writing episodes for Danger and Manhunt in the early 1950s. His scripts caught the attention of Fred Coe, the dynamic producer of NBC's live anthology drama, the Philco-Goodyear Playhouse. Chayefsky's first script for Coe, Holiday Song, won immediate critical acclaim when it aired in 1952. Subsequently, Chayefsky bucked the trend of the anthology writers by insisting that he would write only original dramas, not adaptations. The result was a banner year in 1953. Coe produced six Chayefsky scripts, including Printer's Measure and The Reluctant Citizen. Chayefsky became one of television's best-known writers, along with such dramatists as Tad Mosel, Reginald Rose, and Rod Serling.Chayefsky's stories were notable for their dialogue, their depiction of second-generation Americans, and their infusions of sentiment and humor. They frequently drew on the author's upbringing in the Bronx. The protagonists were generally middle-class tradesmen struggling with personal problems: loneliness, pressures to conform, blindness to their own emotions. The technical limitations of live broadcast suited these dramas. The stories took place in cramped interior settings and were advanced by dialogue, not action. Chayefsky said that he focused on "the people I understand; the $75 to $125 a week kind"; this subject matter struck a sympathetic chord with the mainly urban, middle-class audiences of the time.

Marty, a typical Chayefsky teleplay and one of the most acclaimed of all the live anthology dramas, aired in 1953. Rod Steiger played the lonely butcher who felt that whatever women wanted in a man, "I ain't got it." When Marty finally met a woman, his friends cruelly labeled her "a dog." Marty finally decided that he was a dog himself and had to seize his chance for love. The play ended happily, with Marty arranging a date. Critics compared Marty and other Chayefsky teleplays to the realistic dramas of Arthur Miller and Clifford Odets. In Chayefsky's plays, however, positive endings and celebrations of love tended to emerge from the naturalistic framework. The Chayefsky plays also steered clear of social issues, like most of the anthology dramas.After Marty enjoyed phenomenal success as a Hollywood film, Chayefsky left television in 1956. His exit narrowly preceded the demise of the live dramas, as sponsors began to prefer pre-recorded shows. Even while the live dramas were declining, however, Chayefsky's teleplays found new life. Simon and Schuster published a volume of Chayefsky's television plays. And three of them, in addition to Marty, became Hollywood films: The Bachelor Party (1957) and Middle of the Night (1959), adapted by Chayefsky, and The Catered Affair (1957), adapted by Gore Vidal.

In the 1960s, Chayefsky abandoned the intimate, personal dramas on which he had built his reputation. His subsequent work was often dark and satiric, like the Academy-Award winning film, The Hospital (1971). Network, Chayefsky's send-up of television, marked the apex of his satiric mode. He depicted an institution that had sold its soul for ratings and become "a goddamned amusement park," in the words of news anchor Howard Beale, the movie's main character. Before Chayefsky's death in 1981, he wrote one more screenplay, Altered States (1980), based on his own novel. He refused a script credit, however, due to disagreements with the film's director, Ken Russell.Chayefsky wrote only one television script after 1956, an adaptation of his 1961 play Gideon. His reputation as a television dramatist rests on the eleven scripts he completed for the Philco-Goodyear Playhouse. His influence on the live anthologies was considerable, but he is just as notable for the career he forged after television.

Glenn Erickson on Emily (via DVD Savant):

It's easy enough to just turn one's brain off and enjoy the great acting and funny lines - Chayefsky invents several clever euphemisms to substitute for rough language and at one point even has Charlie call Emily a bitch. She doesn't want to become Americanized, i.e., seduced by Yankee consumer riches and arrogance. He gets to rub her indignation back in her face, by telling her as they break up their relationship, "I want you to remember that when you last saw me, I was unregenerately eating a Hershey bar!" Emily uses these arguments in sophisticated context - Charlie is being ironic and just playing at arrogance - but the signals get mixed anyway.

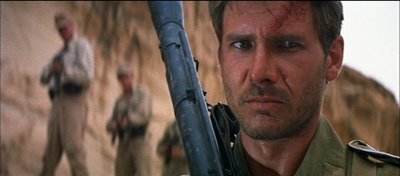

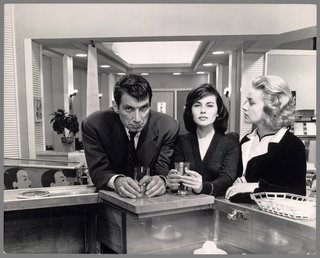

Chayefsky is a brilliant writer and his stylized dialogues are great to listen to. Interestingly enough, this movie, Hospital and Network all resort to the same plot trick - a major character goes nuts and starts seeing visions that warp reality for the other characters.The film is a career highpoint for most of its actors. Garner is all over Charlie Madison, the apex of his winning, smart-ass Maverick persona. James Coburn shapes up as star material with a snappy major supporting role, and Melvyn Douglas is spot-on as the Admiral fighting not for victory but for the betterment of his branch of the service. There's also good playing both farcical and straight from Edward Binns, William Windom, Liz Fraser and Keenan Wynn, who does a great drunk act with Dobie Gillis alumnus Steve Franken. Alan Sues and Judy Carne ( both of Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In) are a camera specialist and "Nameless Broad" respectively; the film may be progressive in some regards, but its females are mostly bimboes. Sharon Tate is said to be visible somewhere. She was or was soon to be Martin Ransohoff's girlfriend.

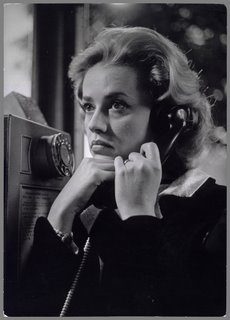

Ransohoff's production is splendid, with excellent B&W photography and clever short-cuts to make us think we're seeing a lot more production value than we are. This and Mary Poppins are Julie Andrews' first films, and she's so good in a mature role that we immediately understand why she felt stifled by her kiddie-nanny career. Emily admits to sleeping around and has no shame ... it's a challenging role and she carries it off with dignity.The only gripe about the physical production are the women's hairstyles: Andrews, Fraser and all of Garner's good-time motor pool girls have poofy 1964 big-hair hairdos ... there's little or no period feeling.

The Americanization of Emily certainly has a different take on D-Day than Saving Private Ryan, even though they share the same attitude about survival on Normandy Beach. Its precocious but suspicious thesis is brilliantly written, and the movie is highly enjoyable. You know Marty, that Paddy Chayefsky can really write.

Director Arthur Hiller provides an interesting commentary with plenty of personal reminiscences. His take on the movie is that the script isn't anti-war, it's just against its glorification, which is fair enough. He does let us know that the U.S. military did not approve of the script and offered zero cooperation. It's interesting that the military will spend taxpayer money to promote itself through movies it feels are good PR for the services, while denying aid to others. I suppose it's no more twisted than spending defense money on recruiting propaganda - I've collected pamphlets sent to my college-age sons which portray the Army as a beer party on the beach with a lot of swimsuit models. That's just the attitude The Americanization of Emily deplores.