Peter's Nite

Vincent Malle (Louis's little brother) via movienet:

Vincent Malle (Louis's little brother) via movienet:

I was still in elementary shool when my brother Louis made Elevator to the Gallows. After all he was barely 24 years old himself. But I remember the buzz in the family and my new status at school when the first reviews came out. Suddenly everybody—including the parents of schoolmates—were my best friends and wanted cinema passes and autographed photos. That was my first brush with fame and it confirmed an already well established love for the cinema.

Over the years, many things have been written about the film, lots of anecdotes about the shoot, about Louis. For example the famous night when Miles Davis recorded the music with a quintet of French musicians in a few hours, improvising each number and sipping champagne with Jeanne Moreau and their jazz-crazy director. By the way, the particular sound he made on the freeway scene was not premeditated. It turns out he lost a bit of his lower lip into the mouthpiece and therefore “blew” differently.

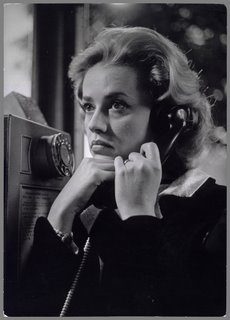

Also the much talked-about scene of Jeanne walking down the Champs Elysées at night, with Henri Decae (the Director of Photography) in a wheelchair and electricians holding battery-activated lamps. Since it was Louis’s first film, the laboratory called the producer the next day saying it was completely black and had to be entirely reshot. Thank God they didn’t, and it remains one of the more significant minimalist night scenes ever. And other directors took notice: So you can shoot at night almost without lights!

Also the much talked-about scene of Jeanne walking down the Champs Elysées at night, with Henri Decae (the Director of Photography) in a wheelchair and electricians holding battery-activated lamps. Since it was Louis’s first film, the laboratory called the producer the next day saying it was completely black and had to be entirely reshot. Thank God they didn’t, and it remains one of the more significant minimalist night scenes ever. And other directors took notice: So you can shoot at night almost without lights!

This brings me to a question a lot of people ask me, especially in America: Was Louis part of the “nouvelle vague” or not? Well, yes and no.

No, because he never belonged to (and was very against) any “movement” or “school” and he certainly was not part of the Cahiers du Cinéma crowd like Truffaut, Godard, Rivette or Chabrol.

But yes, because he shared the same admiration for American cinema that he saw with them at the French Cinématheque of Henri Langlois (John Ford, Nicholas Ray, Douglas Sirk) and also because he was out of the gate before any of them (Truffaut made his first feature nine months after Louis).

So to try to settle it, I would say he was the closest and the most obvious precursor of the New Wave.

Elevator was an enormous success both critically and commercially, won the Prix Louis Delluc (one of France’s most prestigious awards) and definitely launched Jeanne Moreau’s career as a star.

And the music…!

Terrence Rafferty via Criterion:

Terrence Rafferty via Criterion:

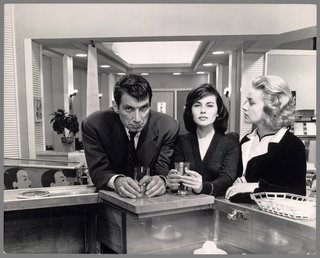

Malle later said of Elevator to the Gallows, “I showed a Paris not of the future but at least a modern city, a world already dehumanized,” a statement that, I think, serves as a useful description of the film itself: not of the future but at least modern. Some of that modernity is on the surface—in the “automated” paraphernalia of the office and the motel, in the glass-and-concrete boxiness of the Carala building, in the sleekness of Julien’s sports car and suit. What’s most deeply modern about the film, though, is an undertone of war weariness and general cynicism, which is most evident in the character of Julien, a veteran of France’s recent wars in Indochina and Algeria. Ronet, who doesn’t have much dialogue, is the very picture of postcolonial tristesse: all haunted eyes and uselessly correct bearing. (He would employ these same resources, and several more, in his indelible portrayal of a suicide in The Fire Within.) And it’s probably not an accident that Malle gave the role of the anomic punk Louis to Poujouly, a young actor best known for playing one of the death-obsessed children in René Clément’s great 1952 antiwar film Forbidden Games.

These characters are not, however, the sort of complex, rounded, infinitely surprising people that Malle would explore with such exhilarating curiosity in films like Murmur of the Heart (1971), Lacombe, Lucien (1974), Atlantic City (1980), and Vanya on 42nd Street (1994). Florence and Julien and the rest are all essentially working parts of a thriller machine, and whatever nuance Malle gives them is just a little oil to keep them from clanking too loudly. The film’s beauty lies in its economy, in its formal rigor (Malle once said that he was torn between Robert Bresson and Alfred Hitchcock, and both influences are apparent here), and in the sly, nearly absurdist humor of the cascading coincidences that doom the homicidal protagonists.

These characters are not, however, the sort of complex, rounded, infinitely surprising people that Malle would explore with such exhilarating curiosity in films like Murmur of the Heart (1971), Lacombe, Lucien (1974), Atlantic City (1980), and Vanya on 42nd Street (1994). Florence and Julien and the rest are all essentially working parts of a thriller machine, and whatever nuance Malle gives them is just a little oil to keep them from clanking too loudly. The film’s beauty lies in its economy, in its formal rigor (Malle once said that he was torn between Robert Bresson and Alfred Hitchcock, and both influences are apparent here), and in the sly, nearly absurdist humor of the cascading coincidences that doom the homicidal protagonists.

And although nowhere close to all of Louis Malle is present in Elevator to the Gallows, the movie does supply a nice ironic metaphor for his unique, bravely eclectic career. This terrific thriller is about the horror of being stuck, trapped, unable to move: that is, about the stasis this filmmaker devoted the rest of his life, and the best of his art, to avoiding.

Vincent Malle (Louis's little brother) via movienet:

Also the much talked-about scene of Jeanne walking down the Champs Elysées at night, with Henri Decae (the Director of Photography) in a wheelchair and electricians holding battery-activated lamps. Since it was Louis’s first film, the laboratory called the producer the next day saying it was completely black and had to be entirely reshot. Thank God they didn’t, and it remains one of the more significant minimalist night scenes ever. And other directors took notice: So you can shoot at night almost without lights!

Terrence Rafferty via Criterion:

These characters are not, however, the sort of complex, rounded, infinitely surprising people that Malle would explore with such exhilarating curiosity in films like Murmur of the Heart (1971), Lacombe, Lucien (1974), Atlantic City (1980), and Vanya on 42nd Street (1994). Florence and Julien and the rest are all essentially working parts of a thriller machine, and whatever nuance Malle gives them is just a little oil to keep them from clanking too loudly. The film’s beauty lies in its economy, in its formal rigor (Malle once said that he was torn between Robert Bresson and Alfred Hitchcock, and both influences are apparent here), and in the sly, nearly absurdist humor of the cascading coincidences that doom the homicidal protagonists.

No comments:

Post a Comment