Nora's Nite

Nora's NiteFusilli pasta with homemade meat sauce, Lemon Torte, Ice Cream

Roger Ebert writing in 1968: The problem here is that real events are being offered as entertainment. A strangler murdered 13 women and now we are asked to take our dates to the Saturday night flick to see why. Gerold Frank's original book was written with the most honorable intentions, I believe, but the movie is something else: A deliberate exploitation of the tragedy of Albert DeSalvo and his victims.

That the killings are being exploited there can be little doubt. Although the film's treatment of the murders is restrained and intelligent, it is being promoted in singularly bad taste. Outside the theater there's a door that flaps open and shut, while lurid photographs of the strangler's victims rotate inside.

What sort of person is attracted by this approach? I can't forget two young girls sitting near me in the theater. Near the film's end, Tony Curtis (as DeSalvo) has a long and difficult scene in which he pantomimes one of the murders. It is compelling, brutal and tragic. And these girls were laughing. They were having the times of their lives. My God. When you see something like this it forces you to rethink your whole approach to the movie.

It will be argued that the film is beneficial and even educational. I am not sure. We are told that Albert DeSalvo literally had a split personality: That most of the time he was a family man, absolutely unaware of his other identity as the strangler. Then what do we learn?

DeSalvo seems to have been one man in a million, a man with a rare psychological and medical history which made him, in a sense, irresponsible for his crimes. What do we learn, except that he was sick? Is our insight into crime -- and the social causes for it -- increased? Hardly. From this point of view, "In Cold Blood" was the worthier film because it dealt with conditions that could have been changed, lives that might have been saved.

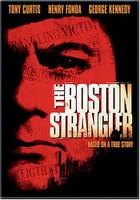

If "The Boston Strangler" is not a public service -- all these "true" crime movies are publicized as noble and responsible undertakings -- then why should we praise it? It serves three other functions: as art, as entertainment and as a commercial venture. As entertainment, it's first-rate. Henry Fonda is a subtle, sensitive lawyer; George Kennedy makes a convincing cop, and Tony Curtis acts better than he has in a decade. There are some fascinating scenes of police work, some dirty words, some sex, some laughs, some suspense and a chase.

Richard Fleischer: The son of famed animator Max Fleischer (Popeye, Betty Boop et. al.), Richard O. Fleischer was a psychology student at Brown University when he dropped out in favor of the Yale Drama Department. At age 21, Fleischer organized a campus theatrical troupe called the Arena Players. In 1942, he went to work for RKO-Pathe in New York, editing the company's weekly newsreels before producing and directing his own short-subject projects, including the March of Time-like This is America and a series of gagged-up silent-film vignettes titled Flicker Flashbacks. In 1946, he headed to Hollywood, there to direct feature films for Pathe's parent studio, RKO Radio; his last short-subject effort was the Oscar-winning Design for Death (1948). At first limited to "B" pictures, Fleischer gained a loyal critical following with such topnotch films as Follow Me Quietly (1949) and The Narrow Margin (1952).

Perhaps sensing that RKO was on its last legs, Fleischer moved on to MGM, then to Walt Disney Studios.

While working for Disney he helmed his first big-budgeter, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954). Firmly established as an action specialist, Fleischer remained in this vein with such profitable projects as The Vikings (1958), These Thousand Hills (1959) and Fantastic Voyage (1966). He also evinced a fondness for crime and suspense pictures, notably Violent Saturday (1955), Compulsion (1959) and The Boston Strangler (1968). While many of his films were box-office bonanzas, he also turned out an equal number of unsuccessful films including Dr. Doolittle (1967) and Che! (1969).A true survivor, Fleischer was able to remain active until the late 1980s, by which time he'd chalked up fewer and fewer hits like The New Centurions (1972) and more and more misses like The Jazz Singer (1980) and Million Dollar Mystery (1987). Though he hasn't made a film since 1990, Richard Fleischer has kept busy as the licensee of his dad's cartoon creation Betty Boop; and in 1994, Fleischer published his sprightly autobiography, Just Tell Me When to Cry. ~ Hal Erickson, All Movie Guide

Edward Anhalt: Born in New York City. After working as a journalist and documentary filmmaker for Pathé and CBS-TV, teamed with his wife Edna Anhalt (née Richards) during WW II to write pulp fiction. After the war, they graduated to writing screenplays for thrillers, beginning with BULLDOG DRUMMOND STRIKES BACK (1947). Anhalt proved himself a versatile, consistently effective (and reputedly speedy) scenarist, superb at contemporary urban thrillers (PANIC IN THE STREETS, 1950), war dramas (THE YOUNG LIONS, 1958), historical epics (BECKET, 1964) and much of everything in between, such as THE MEMBER OF THE WEDDING (1952, also assoc. producer), NOT AS A STRANGER (1955) and THE PRIDE AND THE PASSION (1957).

On his own (or in collaboration with writers other than his wife), some of his non-nominated credits include GIRLS! GIRLS! GIRLS! (1962), WIVES AND LOVERS (1963), BOEING BOEING (1965), THE BOSTON STRANGLER (1968), THE MADWOMAN OF CHAILLOT (1969), JEREMIAH JOHNSON (1972), "QB VII" (TV mini-series, 1974), THE MAN IN THE GLASS BOOTH (1975), LUTHER (1976), GREEN ICE (1981) and THE HOLCROFT COVENANT (1985). During the last years of his career, he worked mainly for television series and made-for-TV movies.

* Writing (Motion Picture Story) 1950: PANIC IN THE STREETS (w. Edna Anhalt)

Nominated for Writing (Motion Picture Story) 1952: THE SNIPER (w. Edna Anhalt)

* Writing (Best Screenplay based on material from another medium) 1964: BECKET

3 nominations, 2 Awards

Was DeSalvo the Strangler? Even though nobody has ever officially been on trial as the Boston Strangler, the public believed that Albert DeSalvo, who confessed in detail to each of the eleven "official" Strangler murders, as well as two others, was the murderer. However, at the time that DeSalvo confessed, most people who knew him personally did not believe him capable of the vicious crimes and today there is a persuasive case to be made that DeSalvo wasn't the killer after all.

CBS News on DeSalvo: Over an 18-month period from 1962 to 1964, the city of Boston was terrorized by a serial killer, the infamous "Boston Strangler." But in 1964, Albert DeSalvo confessed to the brutal killings of 13 women, and authorities and the city at large breathed a collective sigh of relief, believing the killer was finally behind bars.When he confessed, DeSalvo was a patient in a mental hospital, and his confession could not be used against him. With no evidence linking him to any of the 13 murders, DeSalvo was convicted of unrelated crimes and was sentenced to life in prison.

Now, 36 years later, 48 Hours reports that some investigators, as well as the family of one victim, are not sure that DeSalvo was the killer. They believe DeSalvo lied in his confession, and they want to force the state to open the case.

Diane Dodd, the sister of victim Mary Sullivan, says her instincts told her someone got away with murder. Now she and Albert DeSalvo's brother Richard are pushing the state to reopen the long dormant case.They have many allies. Susan Kelly, author of The Boston Stranglers, believes DeSalvo fabricated the entire story. She concedes that his confession was accurate on many details but adds, "the newspapers were an excellent source of information - and it's very interesting to me that the details that Albert got wrong in his confession were identical to the details that the newspapers got wrong."

Kelly thinks several different perpetrators committed the murders.

Robert Ressler, a criminologist and former profiler for the FBI, also believes that it is unlikely that one person is responsible for all the Strangler murders. "You're putting together so many different patterns here that its inconceivable behaviorally that all these could fit one individual," says Ressler.

Despite the theories, without new evidence there is little chance the investigation will lead to answers. To gather that evidence, Dodd agreed to have her sister's body exhumed and re-examined. "This is the last resort. maybe there is something," says Dodd.

Forensics expert James Starrs led the team of independent scientists tha performed the second autopsy on Sullivan.

Although the body had deteriorated, they were able to extract several pieces of evidence that may lead to a positive identification of the killer. "The most promising evidence is a head hair from the pubic region," says Starrs. "We do not expect to find head hairs in the pubic region."Starrs' autopsy also turned up something that may refute DeSalvo's statement that he strangled Mary Sullivan with his bare hands. Starrs found that the hyoid bone in Sullivan's neck was not broken. According to Starrs, that bone would likely have broken if Sullivan had been strangled by hand.

Attorneys Dan Sharp and Elaine Whitfield are helping the families sue the government on the grounds that biological evidence taken is personal property. The State of Massachusetts recently announced that it did find new evidence and will test it. So far the state has refused to share this new evidence, but the families want to be present when the testing is done.

Dodd hopes the newfound evidence can lead to an answer to 36 years of wondering. But she also knows she faces an uphill battle. If it never goes anywhere I'm going to be able to say at least I tried."

Boston Strangler FBI files: DeSalvo was the subject of an FBI unlawful flight to avoid confinement investigation when he escaped from a Massachusetts state mental hospital on February 24, 1967. DeSalvo was being held at the hospital pending appeal of a life sentence for numerous rapes. Local authorities apprehended DeSalvo in Lynn, Massachusetts, the following day. Files contain background information on DeSalvo. A 1961 memo documents an arrest when Desalvo was know as the "Tapester." At that time he was accused of posing as a talent scout for a modeling agency. He would ring door bells looking for young women who he would offer a modeling job, if they passed a measuring test.

No comments:

Post a Comment