Peter's Nite

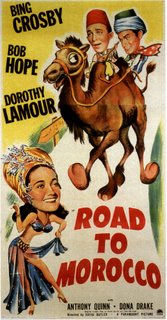

Peter's Nite"Road to Morocco" lyrics via mcckc:

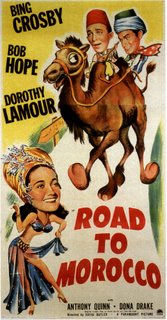

We're off on the road to Morocco

This camel is tough on the spine (hit me with a band-aid, Dad)

Where they're goin', why we're goin', how can we be sure

I'll lay you eight to five that we'll meet Dorothy Lamour (yeah, get in line)

Off on the road to Morocco

Hang on till the end of the line (I like your jockey. Quiet)

I hear this country's where they do the dance of the seven veils

We'd tell you more (uh-ah) but we would have the censor on our tails (good boy)

We certainly do get around

Like Webster's Dictionary we're Morocco bound

We certainly do get around

Like a complete set of Shakespeare that you get

in the corner drugstore for a dollar ninety-eight

We're Morocco bound

Or, like a volume of Omar Khayyam that you buy in the

department store at Christmas time for your cousin Julia

We're Morocco bound

(we could be arrested)

From 100 Reasons to Toast Bob Hope via USA TODAY:

From 100 Reasons to Toast Bob Hope via USA TODAY:

1942. "We couldn't get a real camel for (Road to Morocco), so the makeup department took one of Crosby's horses, put two big lumps on its back, long shaggy hair all over it, and made its front legs bend inward at the knees. It looked just like one of Crosby's horses."

1945. "Crosby's making nothing but costume pictures now. Any time you see him in a movie with his hat off and his waistline below 40 inches ... believe me, it's a costume picture."

1945's Road to Utopia. An elderly Hope, hearing Crosby's approaching singing voice for the first time in 35 years, "Who'd be selling fish at this hour?"

Larry King interview with Bob Hope via CNN:

KING: Encino, California for Bob Hope, hello?

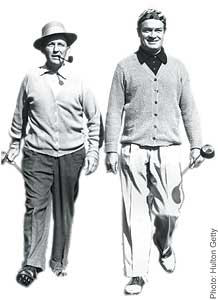

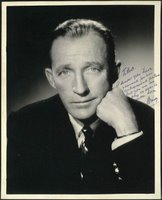

CALLER: Good evening. My question for Mr. Hope is what brought about his first meeting with Bing Crosby? And could he tell that first time you meet him that there would be the chemistry that would exist between them for so many years?

HOPE: We played the Capitol Theater in New York, which was a big picture house. And Bing and I were featured. Abe Lyman (ph) was the orchestra. And we did three and four shows a day. And it got kind of boring, me just introducing them. So we started to ad lib. And we built up a couple of routines, like the president and the Pepsi Cola Company meeting the president of Coca-Cola on the street. We'd say hello and then we'd belch in the mike. And then I'd belch again and say bigger bottle with Pepsi.

HOPE: We played the Capitol Theater in New York, which was a big picture house. And Bing and I were featured. Abe Lyman (ph) was the orchestra. And we did three and four shows a day. And it got kind of boring, me just introducing them. So we started to ad lib. And we built up a couple of routines, like the president and the Pepsi Cola Company meeting the president of Coca-Cola on the street. We'd say hello and then we'd belch in the mike. And then I'd belch again and say bigger bottle with Pepsi.

And we worked up this routine. Now when I got out here in '37, Bing invited me down to Delmar. And we did the routine down there. And somebody saw it and went right back to Paramount and said you got to put these guys together. Boy, they were -- they didn't know that we had rehearsed it five years before for a couple of weeks. And we stayed. We had a picture called "Flight to Singapore" and changed it to "Road to Singapore." And that was the start of the thing.

KING: In retrospect, Bob, as you looked at it, what do you think was the magic with the two of you?

HOPE: Well, I don't know.

KING: Why did it work?

HOPE: I don't know, Larry. I think it was the fact that we had a great respect for each other and we both understood how to feed each other. And it was more fun. I've never had that much fun anywhere making a picture. It was just -- and you never knew what was going to happen because we used to rat out at each other and steal a punchline before he was supposed to take it. He'd do the same thing to me.

And it was a shambles all the way. It was fun. And the people knew what we were doing.

KING: You did have, I guess you're aware of this, a wonderful attitude. There was a Bob Hope attitude when he walked on a stage, that was seemingly oblivious to everything. I mean, this was going to be just another easy night. Was that outward? For example inward, are you still nervous when you do a monologue?

HOPE: No, I'm not. I'm only concerned, Larry, that the fear of that I'll forget something. You know, when I go to do a personal appearance. And that's the only thing. And a lot of times I do forget because -- especially because I try to do fresh, new things, you know, like I did a whole routine down in Cap (ph) over the weekend. And I said I don't like what's going in Washington because I hate -- you know, I hate when the foreign policy is funnier than I am. And Congress is pretty upset because they hate it when things get screwed up and they don't have a hand in it.

KING: We go to Tallahassee, Florida, hello.

CALLER: Perhaps no other person has been in a better position to see the progress of the American GI. Is there any difference between the GIs of my era and Vietnam from -- to World War II to the present?

CALLER: Perhaps no other person has been in a better position to see the progress of the American GI. Is there any difference between the GIs of my era and Vietnam from -- to World War II to the present?

KING: Good question.

HOPE: I don't think so. Last Monday, I was up near the DMZ with Brooke Shields and this little Gloria gal from the Miami Sound Machine. And we did a show -- we went up there by helicopter and did a show for 3,000 GIs. And they're the same way. They love the gals and they love the jokes.

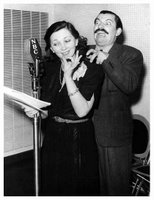

Bob Hope regular Jerry Colonna:

Bob Hope regular Jerry Colonna:

Jerry was born Gerardo Colonna in Boston on September 17, 1904, of Italian immigrant parents. As a little boy he admired his grandfather's enormous moustache ("You could see it from the back!") so much that he often painted one on his upper lip with axle grease. As soon as he could manage it, he grew a "baffi" of his own. Jerry was extremely gifted musically, and he loved jazz, beginning as a drummer then finding his metier in the trombone.

Moving to New York, he became a fixture in orchestras on major radio shows and in the top big bands. At one point he was named one of the five best trombonists in the country.

In the late 30's Jerry's career took an unexpected turn. Comedian Minerva Pious, who played Mrs. Nussbaum on the Fred Allen show, loved Jerry's off-stage antics (he had received so many warnings from CBS for his pranks that he was finally put on perpetual notice. But they never actually fired him -- he was too good a trombonist). Pious decided that Fred Allen, a workaholic, needed a laugh, so she convinced him that Jerry was a brilliant operatic tenor and that Fred should give him an audition. When Jerry gave out with an ear-splitting "You're My Everything," Fred literally fell to the floor laughing and gave him a few guest spots on the show. These led to movie roles, and to the Kraft Music Hall, hosted by Bing Crosby. Bing took Minerva Pious' in-house joke to new lengths by announcing publicly that Giovanni Colonna, one of the greatest living baritones (!) would make his American radio debut on the show. After that broadcast, a number of classical music critics stopped talking to Bing altogether. The following summer, following an appearance at the Del Mar racetrack clubhouse, Jerry was approached by Bob Hope, and radio history was begun.

In the late 30's Jerry's career took an unexpected turn. Comedian Minerva Pious, who played Mrs. Nussbaum on the Fred Allen show, loved Jerry's off-stage antics (he had received so many warnings from CBS for his pranks that he was finally put on perpetual notice. But they never actually fired him -- he was too good a trombonist). Pious decided that Fred Allen, a workaholic, needed a laugh, so she convinced him that Jerry was a brilliant operatic tenor and that Fred should give him an audition. When Jerry gave out with an ear-splitting "You're My Everything," Fred literally fell to the floor laughing and gave him a few guest spots on the show. These led to movie roles, and to the Kraft Music Hall, hosted by Bing Crosby. Bing took Minerva Pious' in-house joke to new lengths by announcing publicly that Giovanni Colonna, one of the greatest living baritones (!) would make his American radio debut on the show. After that broadcast, a number of classical music critics stopped talking to Bing altogether. The following summer, following an appearance at the Del Mar racetrack clubhouse, Jerry was approached by Bob Hope, and radio history was begun.

Jerry's recordings ("I have destroyed many beautiful songs.") are collected today by connoisseurs of madcap comedy. He is probably best known for his hysterical versions of "On The Road To Mandalay" and "Ebb Tide" (where most recordings of the latter began with the sounds of surf and seagulls, Colonna's also includes chickens).

Jerry's recordings ("I have destroyed many beautiful songs.") are collected today by connoisseurs of madcap comedy. He is probably best known for his hysterical versions of "On The Road To Mandalay" and "Ebb Tide" (where most recordings of the latter began with the sounds of surf and seagulls, Colonna's also includes chickens).

Jerry's hobbies included riding his cowponies, collecting guns (he was a crack shot with a Colt .45) and composing music ("Along The Dixie Hi-Fi-Way," an album of his tunes, was released in 1956).

Jerry left the Bob Hope show as a regular around 1950, although he continued to join Bob for the Christmas shows and occasional TV specials. In the mid-50's he achieved yet another sort of immortality by recording the voice of the March Hare in Disney's "Alice In Wonderland," with Ed Wynn as the Mad Hatter.

"Notes on Road to Morocco" via Moviediva:

Hope and Crosby enjoyed themselves ad libbing so much, that Dorothy Lamour gave up memorizing her lines, and decided that getting a good’s night sleep so she could keep up with the improvised wordplay was the best preparation possible. Just because the dialogue was not in the script, didn’t mean that someone didn’t write it, since Hope and Crosby both brought in their radio gag writers to punch up the lines. The director conceded, “You know, I really shouldn’t take any money for this job. All I do is say ‘Stop’ and ‘Go.’” They genuinely seemed to enjoy each other’s company and their friendship, on stage and on the golf course, would continue the rest of their lives. The Road to Singapore, as the film was eventually titled was the first of the 7 Road pictures they would make together. The huge success of the "Road" films was instrumental to Bob Hope's status from 1941-1953 as one of the top 10 box office draws (except for one year). The second "Road" film (…to Zanzibar) was yet another script plucked off a dusty shelf, but the third one, The Road to Morocco, was original material, tailored to Hope and Crosby.

Hope and Crosby enjoyed themselves ad libbing so much, that Dorothy Lamour gave up memorizing her lines, and decided that getting a good’s night sleep so she could keep up with the improvised wordplay was the best preparation possible. Just because the dialogue was not in the script, didn’t mean that someone didn’t write it, since Hope and Crosby both brought in their radio gag writers to punch up the lines. The director conceded, “You know, I really shouldn’t take any money for this job. All I do is say ‘Stop’ and ‘Go.’” They genuinely seemed to enjoy each other’s company and their friendship, on stage and on the golf course, would continue the rest of their lives. The Road to Singapore, as the film was eventually titled was the first of the 7 Road pictures they would make together. The huge success of the "Road" films was instrumental to Bob Hope's status from 1941-1953 as one of the top 10 box office draws (except for one year). The second "Road" film (…to Zanzibar) was yet another script plucked off a dusty shelf, but the third one, The Road to Morocco, was original material, tailored to Hope and Crosby.

This is considered the best of the "Road" pictures. The formula for success includes topical humor similar to that incorporated into Hope’s radio show. The director of this film, David Butler, was well-suited to the comic task, having grown up at Mack Sennett’s slapstick comedy studio in the silent era, and he knew both how to structure a comic scene and when to let the stars wing-it. Rehearsals lost some of the comic spontaneity, so Butler said, “I’d always let the camera run, and we got some of our funniest stuff after the scene was over. I’d even let the camera roll until they got off the set, or walked out, or whatever happened.” This paid off best in the scene where a cranky camel spits in Bob’s eye, and Bing’s laughter shows his surprise. But, as a former stuntman, Butler also volunteered the rather sedentary Hope and Crosby for a thrill or two they would have preferred to avoid, as when a stampede of horses got out of hand, and the stars narrowly escaped being trampled.

This is considered the best of the "Road" pictures. The formula for success includes topical humor similar to that incorporated into Hope’s radio show. The director of this film, David Butler, was well-suited to the comic task, having grown up at Mack Sennett’s slapstick comedy studio in the silent era, and he knew both how to structure a comic scene and when to let the stars wing-it. Rehearsals lost some of the comic spontaneity, so Butler said, “I’d always let the camera run, and we got some of our funniest stuff after the scene was over. I’d even let the camera roll until they got off the set, or walked out, or whatever happened.” This paid off best in the scene where a cranky camel spits in Bob’s eye, and Bing’s laughter shows his surprise. But, as a former stuntman, Butler also volunteered the rather sedentary Hope and Crosby for a thrill or two they would have preferred to avoid, as when a stampede of horses got out of hand, and the stars narrowly escaped being trampled.

The costumes, as for all Paramount “A” films, were designed by Edith Head, who at this point in her career worked on between 40 and 50 films a year. She enjoyed working on the Road films, and wrote in her autobiography, “I didn’t have to worry about authenticity. If somebody wrote and said, ‘Edith, in Morocco they don’t wear headdresses like that,’ I didn’t give a damn. If Bob Hope wanted to wear it because it was funny, he wore it.” (Head). Hope loved dressing up and Crosby hated it. Lamour, who had started in sarongs (she was sewn into them, so they wouldn’t untie) loved the exotic glamour of films like Road to Morocco. “Bob has a special place in my heart for what he did for my costumes in the Road pictures. It was his enthusiasm that really inspired everyone else to get into the spirit of the Roads. There were chaotic plots and gags and lavish sets and great music, but Bob Hope pulled it all together.” (Head).

The costumes, as for all Paramount “A” films, were designed by Edith Head, who at this point in her career worked on between 40 and 50 films a year. She enjoyed working on the Road films, and wrote in her autobiography, “I didn’t have to worry about authenticity. If somebody wrote and said, ‘Edith, in Morocco they don’t wear headdresses like that,’ I didn’t give a damn. If Bob Hope wanted to wear it because it was funny, he wore it.” (Head). Hope loved dressing up and Crosby hated it. Lamour, who had started in sarongs (she was sewn into them, so they wouldn’t untie) loved the exotic glamour of films like Road to Morocco. “Bob has a special place in my heart for what he did for my costumes in the Road pictures. It was his enthusiasm that really inspired everyone else to get into the spirit of the Roads. There were chaotic plots and gags and lavish sets and great music, but Bob Hope pulled it all together.” (Head).

The film was promoted by tacking cards to drinking fountains reading, “Thirsty for entertainment? See what happens when Bob Hope chases Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour to a desert oasis on the Road to Morocco.” In fact, the best promotion for the film were the stars radio programs, many of which, by this time, Hope was doing from Army training bases across the country.

BBC on the 'Road' Films:

The pairing of Crosby and Hope was inspired, with the two men having an instant chemistry. They were forever ad-libbing, generally at each other's expense, and trying to outdo each other to the point where Lamour wondered why she ever bothered learning the scripts for the films. Lamour herself was the perfect foil for Hope and Crosby - beautiful and exotic and equally at home singing with Crosby or setting up jokes for Hope.

The pairing of Crosby and Hope was inspired, with the two men having an instant chemistry. They were forever ad-libbing, generally at each other's expense, and trying to outdo each other to the point where Lamour wondered why she ever bothered learning the scripts for the films. Lamour herself was the perfect foil for Hope and Crosby - beautiful and exotic and equally at home singing with Crosby or setting up jokes for Hope.

I was the happiest and highest-paid straight-woman in the business.

- Dorothy Lamour

The plots of the six films - insomuch as they had a plot - were very similar. Crosby was a con artist or playboy of some description, with Hope as his unwilling sidekick. The pair's failed attempts at romance or moneymaking would lead to them fleeing America and taking refuge in some exotic location, where they would stumble across Lamour dressed in a sarong1. Hope and Crosby would vie for the affections of Lamour, all the while avoiding whatever trouble they were in to start with, plus whatever extra trouble they got themselves into. Crosby's charm and melodious singing would eventually win the girl, leaving Hope with only wisecracks and one-liners to console him.

Road to Morocco marked the Road... films hitting their stride and it was nominated for two Oscars: Best Screenplay (Frank Butler and Don Hartman) and Best Sound Recording (Loren L Ryder). One of the film's funniest moments, however, was completely unscripted. In a scene with Hope, Crosby and a camel, the camel decided to spit heavily in Hope's face. Fortunately, the cameras were rolling and the director was so amused by the expressions on the actors' faces that he kept the shot, with Crosby complimenting the camel on its impeccable taste.

Road to Morocco marked the Road... films hitting their stride and it was nominated for two Oscars: Best Screenplay (Frank Butler and Don Hartman) and Best Sound Recording (Loren L Ryder). One of the film's funniest moments, however, was completely unscripted. In a scene with Hope, Crosby and a camel, the camel decided to spit heavily in Hope's face. Fortunately, the cameras were rolling and the director was so amused by the expressions on the actors' faces that he kept the shot, with Crosby complimenting the camel on its impeccable taste.

The film also saw an increase in the self-referential and slightly surreal moments that were a staple of the Road... films. For example, the film features a camel remarking that 'this is the screwiest picture I was ever in'. The film also features Hope as the ghostly Aunt Lucy, who appears to remind Peters of his obligations to his friend.

The film also saw an increase in the self-referential and slightly surreal moments that were a staple of the Road... films. For example, the film features a camel remarking that 'this is the screwiest picture I was ever in'. The film also features Hope as the ghostly Aunt Lucy, who appears to remind Peters of his obligations to his friend.

"What's Sarong with this Picture?" by Ethan de Seife via SensesofCinema:

In 1946, just prior to the production of Paramount's mystery-comedy My Favorite Brunette (Elliott Nugent, 1947), Dorothy Lamour, with the full assistance of the studio's publicity department, staged a memorable stunt. She publicly burned a sarong, the skimpy South Seas garment with which she had been inseparably associated since her first starring role, in Paramount's 1936 tropical romance The Jungle Princess (Wilhelm Thiele) (Head and Calistro, 67). Between The Jungle Princess and My Favorite Brunette, her busiest period as an actress, Lamour had appeared in 34 feature films, in the process establishing herself as Paramount's top female box office attraction. Lamour appeared in a sarong in 11 of those films, meaning that fully two-thirds of her roles during that ten-year span did not call for her to wrap herself in any manner of South Seas attire. But there was something indelible about the connection between Lamour and her trademark garment: audiences seemed to remember her not for the variety of roles she played, but for those roles in which she appeared in a revealing sarong.

In 1946, just prior to the production of Paramount's mystery-comedy My Favorite Brunette (Elliott Nugent, 1947), Dorothy Lamour, with the full assistance of the studio's publicity department, staged a memorable stunt. She publicly burned a sarong, the skimpy South Seas garment with which she had been inseparably associated since her first starring role, in Paramount's 1936 tropical romance The Jungle Princess (Wilhelm Thiele) (Head and Calistro, 67). Between The Jungle Princess and My Favorite Brunette, her busiest period as an actress, Lamour had appeared in 34 feature films, in the process establishing herself as Paramount's top female box office attraction. Lamour appeared in a sarong in 11 of those films, meaning that fully two-thirds of her roles during that ten-year span did not call for her to wrap herself in any manner of South Seas attire. But there was something indelible about the connection between Lamour and her trademark garment: audiences seemed to remember her not for the variety of roles she played, but for those roles in which she appeared in a revealing sarong.  By publicizing the stunt, the studio was offering a non-sarong-clad Lamour to the public, as well as simultaneously reminding them that Dorothy Lamour and the sarong would be forever united. The very act of burning the sarong could only serve as a reminder that Lamour's sarong pictures were extremely popular. Lamour was always presented in the context of her trademark attire. Despite the stunt, Lamour would don the sarong again at least four more times in her long career.

By publicizing the stunt, the studio was offering a non-sarong-clad Lamour to the public, as well as simultaneously reminding them that Dorothy Lamour and the sarong would be forever united. The very act of burning the sarong could only serve as a reminder that Lamour's sarong pictures were extremely popular. Lamour was always presented in the context of her trademark attire. Despite the stunt, Lamour would don the sarong again at least four more times in her long career.

Lamour's star image was somewhat unusual in that, from her first starring role, the studio found an image that clicked with the public. Her frequent declarations that she was fed up with wearing sarongs indicate that this image clicked all too well. Her track record at the box office showed that the films in which Lamour did not appear in a sarong reaped less money than the ones in which she did.

Peter's Nite

Peter's NiteFrom 100 Reasons to Toast Bob Hope via USA TODAY:

HOPE: We played the Capitol Theater in New York, which was a big picture house. And Bing and I were featured. Abe Lyman (ph) was the orchestra. And we did three and four shows a day. And it got kind of boring, me just introducing them. So we started to ad lib. And we built up a couple of routines, like the president and the Pepsi Cola Company meeting the president of Coca-Cola on the street. We'd say hello and then we'd belch in the mike. And then I'd belch again and say bigger bottle with Pepsi.

CALLER: Perhaps no other person has been in a better position to see the progress of the American GI. Is there any difference between the GIs of my era and Vietnam from -- to World War II to the present?

Bob Hope regular Jerry Colonna:

In the late 30's Jerry's career took an unexpected turn. Comedian Minerva Pious, who played Mrs. Nussbaum on the Fred Allen show, loved Jerry's off-stage antics (he had received so many warnings from CBS for his pranks that he was finally put on perpetual notice. But they never actually fired him -- he was too good a trombonist). Pious decided that Fred Allen, a workaholic, needed a laugh, so she convinced him that Jerry was a brilliant operatic tenor and that Fred should give him an audition. When Jerry gave out with an ear-splitting "You're My Everything," Fred literally fell to the floor laughing and gave him a few guest spots on the show. These led to movie roles, and to the Kraft Music Hall, hosted by Bing Crosby. Bing took Minerva Pious' in-house joke to new lengths by announcing publicly that Giovanni Colonna, one of the greatest living baritones (!) would make his American radio debut on the show. After that broadcast, a number of classical music critics stopped talking to Bing altogether. The following summer, following an appearance at the Del Mar racetrack clubhouse, Jerry was approached by Bob Hope, and radio history was begun.

Jerry's recordings ("I have destroyed many beautiful songs.") are collected today by connoisseurs of madcap comedy. He is probably best known for his hysterical versions of "On The Road To Mandalay" and "Ebb Tide" (where most recordings of the latter began with the sounds of surf and seagulls, Colonna's also includes chickens).

Hope and Crosby enjoyed themselves ad libbing so much, that Dorothy Lamour gave up memorizing her lines, and decided that getting a good’s night sleep so she could keep up with the improvised wordplay was the best preparation possible. Just because the dialogue was not in the script, didn’t mean that someone didn’t write it, since Hope and Crosby both brought in their radio gag writers to punch up the lines. The director conceded, “You know, I really shouldn’t take any money for this job. All I do is say ‘Stop’ and ‘Go.’” They genuinely seemed to enjoy each other’s company and their friendship, on stage and on the golf course, would continue the rest of their lives. The Road to Singapore, as the film was eventually titled was the first of the 7 Road pictures they would make together. The huge success of the "Road" films was instrumental to Bob Hope's status from 1941-1953 as one of the top 10 box office draws (except for one year). The second "Road" film (…to Zanzibar) was yet another script plucked off a dusty shelf, but the third one, The Road to Morocco, was original material, tailored to Hope and Crosby.

This is considered the best of the "Road" pictures. The formula for success includes topical humor similar to that incorporated into Hope’s radio show. The director of this film, David Butler, was well-suited to the comic task, having grown up at Mack Sennett’s slapstick comedy studio in the silent era, and he knew both how to structure a comic scene and when to let the stars wing-it. Rehearsals lost some of the comic spontaneity, so Butler said, “I’d always let the camera run, and we got some of our funniest stuff after the scene was over. I’d even let the camera roll until they got off the set, or walked out, or whatever happened.” This paid off best in the scene where a cranky camel spits in Bob’s eye, and Bing’s laughter shows his surprise. But, as a former stuntman, Butler also volunteered the rather sedentary Hope and Crosby for a thrill or two they would have preferred to avoid, as when a stampede of horses got out of hand, and the stars narrowly escaped being trampled.

The costumes, as for all Paramount “A” films, were designed by Edith Head, who at this point in her career worked on between 40 and 50 films a year. She enjoyed working on the Road films, and wrote in her autobiography, “I didn’t have to worry about authenticity. If somebody wrote and said, ‘Edith, in Morocco they don’t wear headdresses like that,’ I didn’t give a damn. If Bob Hope wanted to wear it because it was funny, he wore it.” (Head). Hope loved dressing up and Crosby hated it. Lamour, who had started in sarongs (she was sewn into them, so they wouldn’t untie) loved the exotic glamour of films like Road to Morocco. “Bob has a special place in my heart for what he did for my costumes in the Road pictures. It was his enthusiasm that really inspired everyone else to get into the spirit of the Roads. There were chaotic plots and gags and lavish sets and great music, but Bob Hope pulled it all together.” (Head).

The pairing of Crosby and Hope was inspired, with the two men having an instant chemistry. They were forever ad-libbing, generally at each other's expense, and trying to outdo each other to the point where Lamour wondered why she ever bothered learning the scripts for the films. Lamour herself was the perfect foil for Hope and Crosby - beautiful and exotic and equally at home singing with Crosby or setting up jokes for Hope.

Road to Morocco marked the Road... films hitting their stride and it was nominated for two Oscars: Best Screenplay (Frank Butler and Don Hartman) and Best Sound Recording (Loren L Ryder). One of the film's funniest moments, however, was completely unscripted. In a scene with Hope, Crosby and a camel, the camel decided to spit heavily in Hope's face. Fortunately, the cameras were rolling and the director was so amused by the expressions on the actors' faces that he kept the shot, with Crosby complimenting the camel on its impeccable taste.

The film also saw an increase in the self-referential and slightly surreal moments that were a staple of the Road... films. For example, the film features a camel remarking that 'this is the screwiest picture I was ever in'. The film also features Hope as the ghostly Aunt Lucy, who appears to remind Peters of his obligations to his friend.

In 1946, just prior to the production of Paramount's mystery-comedy My Favorite Brunette (Elliott Nugent, 1947), Dorothy Lamour, with the full assistance of the studio's publicity department, staged a memorable stunt. She publicly burned a sarong, the skimpy South Seas garment with which she had been inseparably associated since her first starring role, in Paramount's 1936 tropical romance The Jungle Princess (Wilhelm Thiele) (Head and Calistro, 67). Between The Jungle Princess and My Favorite Brunette, her busiest period as an actress, Lamour had appeared in 34 feature films, in the process establishing herself as Paramount's top female box office attraction. Lamour appeared in a sarong in 11 of those films, meaning that fully two-thirds of her roles during that ten-year span did not call for her to wrap herself in any manner of South Seas attire. But there was something indelible about the connection between Lamour and her trademark garment: audiences seemed to remember her not for the variety of roles she played, but for those roles in which she appeared in a revealing sarong.

By publicizing the stunt, the studio was offering a non-sarong-clad Lamour to the public, as well as simultaneously reminding them that Dorothy Lamour and the sarong would be forever united. The very act of burning the sarong could only serve as a reminder that Lamour's sarong pictures were extremely popular. Lamour was always presented in the context of her trademark attire. Despite the stunt, Lamour would don the sarong again at least four more times in her long career.

No comments:

Post a Comment