Stuart's Nite

Stuart's NiteKoo Koo Roo chicken and salad hits the spot

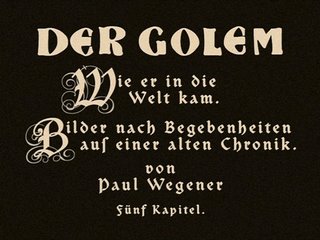

Cathy Gelbin on the Golem:

The term "Golem" first appears in the Hebrew Scriptures. In Psalm 139:16 it connotes a shapeless mass, perhaps an embryo, while a derivative of the root in Isaiah 49:21 refers to female infertility.[1] Medieval Jewish mystics adopted the term to describe an artificial man created via Cabbalistic ritual.A Polish-Jewish folk-tale tradition centered around the creation of a Golem arose around 1600 and made its way into German literary Romanticism two hundred years later.[2] Writing in the age of Jewish emancipation, Christian authors such as Achim von Arnim, ETA Hoffmann and others used the Golem to reflect the common perception of Jews as uncanny and corrupt. A second Jewish folk-tale tradition attributing the making of a Golem to the sixteenth-century Rabbi Löw of Prague developed around 1750. This tradition came to dominate the German literary imagination at the end of the nineteenth century and has informed most Golem renditions since.

...

Anti-Jewish stereotypes also mark the portrayal of Miriam as the dark and seductive Jewish woman, while Christian women at the court shy away from the Golem's advances. Even more strongly, the blonde girls at the end of the film signify innocence and virginity, though the apple implies the danger of temptation emanating from all femininity.Yet the polarity between the images of Jewish and Christian women is blatant. Outside the ghetto walls, the Golem sees a mother and child bringing flowers to a statue of the Virgin Mary and her baby Jesus. Significantly, the name of the Christian Madonna represents the Greek transliteration of the Hebrew name Miriam.

The Jewish woman thus exemplifies the destructive allure of the female sex unless restrained by Christian chastity, domesticity and maternity.The soulless Golem equally contrasts with the naturalised image of mother and child who are bathed in light and aligned with the Christian world. This construction evokes the claim by Tertullian that "the soul is by nature Christian," an assertion still cited in the Twentieth Century.[18]

Whether intended or not, however, the juxtaposition between the motherless Golem and the Christian Messiah also reopens the question of the latter's unclear paternal origins. The visual association between both figures implicitly parodies the assertion of Christianity as "natural," a term hardly descriptive of the immaculate conception.

The film is a free download here.

BBC on Wegner and Golum:

The German actor and director Paul Wegener (1874 - 1948) made many films, but he's particularly remembered for his three films centred around the Jewish legend of the Golem1. He first heard about it while working in Prague on his film The Student of Prague in 1913, and shortly afterwards he set to work making a new film inspired by the legend.According to the legend of Golem, the Emperor Rudolph II was about to issue an edict against the Jews of Prague. Rabbi Judah Low Ben Bezalel2, one of the ghetto's elders, created a Golem, a clay statue brought to life by magic, to defend the Jews from the pogrom. The legend has several variants, differing in detail. Sometimes the Golem is brought to life by a magic word written on his forehead; erase the word, and he ceases to live. Other versions mention a hot ball placed in the Golem's skull, or a tablet with the name of God written on it put in the Golem's mouth. In Wegener's films the Golem is brought to life by a shem, a 'Star of David' pendant concealing a piece of paper with the magic word on it. Remove the shem, and the Golem is rendered inert.

Wegener played the Golem himself in all three films. At over six feet tall, with an expressive face, he was well-suited for the part. He continued to make films and perform on stage throughout his life, even when Germany was under Nazi rule. However, he was plagued with ill health, and he collapsed on stage a few days before his death, a trouper to the end.

Film Monthly:

THE GOLEM is a film of great power, as hypnotic as a German Expressionist vision of life as a waking dream. The dim light and looming shadow were photographed by Karl Freund, who also shot two German Expressionist masterpieces: Fritz Lang's Metropolis and F.W. Murnau's The Last Laugh. Freund later emigrated to America and eventually became the head cameraman for I Love Lucy.

Hans Poelzig's stylized sets convey the claustrophobia of ghetto life, with curved stone walls and sharply pointed roofs. The two sets of circular stairs the characters climb down to enter the rabbi's study look like the twin chambers of a human heart.However, THE GOLEM is not really a German Expressionist story; it is more a combination of Jewish mysticism and fairy tale. Director Wegener portrays the supernatural elements of the story without irony or psychological explanation, as if we were truly in medieval Prague, when people would have believed that an amulet and an incantation could bring a clay figure to life.

Production designer & architect Hans Poelzig via Wikipedia:

Hans Poelzig (April 30, 1869 Berlin - June 14, 1936 Berlin) was a German architect, painter, and set designer active in the Weimar years.

After finishing his architectural eduation around the turn of the century, Poelzig designed many industrial buildings. For an industrial fair in 1911, he designed the Upper Silesia Tower in Posen 51.2 m tall, which later became the water tower. He was eventually appointed city architect of Dresden in 1916.

Poelzig was also known for his distinctive 1919 interior redesign of the Berlin Grosses Schauspielhaus for Weimar impressario Max Reinhardt, and for his vast architectural set designs for the 1925 UFA film production of The Golem. (Poelzig mentored Edgar Ulmer on that film; when Ulmer directed the 1934 film noir Universal Studios production of "The Black Cat", he returned the favor by naming the architect-Satanic-high-priest villain character "Hjarmal Poelzig", played by Boris Karloff.)With his Weimar architect contemporaries like Bruno Taut and Ernst May, Poelzig's work developed through Expressionism and the New Objectivity in the mid-1920s before arriving at a more conventional, economical style. In the 1920s he ran the "Studio Poelzig" in partnershp with his wife Marlene. Poelzig also designed the 1929 Broadcasting House in the Berlin suburb of Charlottenburg, a landmark of architecture, Cold War history, and engineering history.

Poelzig's single best-known building is the enormous and legendary I.G. Farben Building, completed in 1931 as the administration building for IG Farben in Frankfurt am Main, now known as the Poelzig Building at Goethe University. In March 1945 the building was occupied by American Allied forces under Eisenhower, became his headquarters, and remained in American hands until 1995. Some of his designs that were never built included one for the Palace of the Soviets and one for the League of Nations headquarters at Geneva.

Poelzig died in Berlin in June 1936, shortly before his planned departure for Ankara.

No comments:

Post a Comment