Peter's Nite

Peter's NiteSalad, Pizza, Chocolate Tote

Films and Filming, 1962: "The Trial of Orson Welles" by Enrique Martinez via Wellesnet:

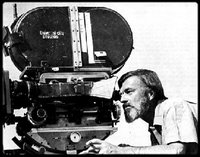

The old d'Orsay station, fallen into decay with the passing of time, with its enormous and dirty vault, its modern-style lamps, its twisted staircases, and its vastness truly represents the all-powerful endemic laws which sow the seeds of terror and death amongst the men who live within its shade without knowing the sun-light and infinite horizons which extend beyond the enomrous and filthy walls which surround them. All this of course is part of Welles' special baroque manner in which symbolism abounds without, however, at any point touching on that of Fellini, for example. Everything is twisted, exuberant, cosmic - the enomrous bed of the lawyer with its dragons and tapestry, the mirrors, the archives, the office files, the lamp shades that drop dust.And what about Orson Welles, the director? The impression that he makes in person correspsonds exactly to the legend that has grown up around him. Big, strong and stout, deep voiced and with his enormous cigar, walking along in the midst of technicians, cables and half-assembled sets, he gives the impression of a lion shut in behind the bars of his cage.

He makes the actors rehearse a good deal. He takes them into a corner away from everyone else for an hour. Orson talks to them, repeats him aims, tells them what he expects of them even down to the tone of voice. It is not a question of seeing whether the actors have learnt the script by heart. It is a question of introducing them to the atmosphere of the scene, the character of the role and its reality. Sometimes an hour is not long enough and Welles rehearses for four, six or even ten hours. (I do not know whether it is usual with him but while I was there shooting was held up for two days because Welles was rehearsing with Romy Schneider and Tony Perkins for a whole day, from noon till seven in the evening.) The actor plays a very important part in Welles' system of direction and on this account the attention that he dedicates to his players is very great.

Once he is satisfied with an actor's work, Welles goes on to rehearse the camera movements and speed. Examining the set up he modifies what has been planned, changing the direction and intensity of the lights. Once all this has been arranged to his satisfaction, he rehearses two or three times the placing of the actors and then rapidly prepares to shoot. His voice can be heard for miles around. 'Motor-action' (the word action is pronounced in a very special way-half American, half French). Rarely does Welles take a scene more than two or three times. Generally the first take is alright. He repeats it in case of an accident during the developing of the film. At times, of course, there is an exception. On one occasion he had to repeat a very simple scene 13 times. Not because the camera movement was difficult or because the actor's script was tricky. No. Simply because Orson Welles was in good spirits. Every time that Perkins began to speak his lines, Welles made faces and funny gestures to make him laugh. And, inevitably, Perkins laughed. And Welles' guffaws made the arc lights above the set dance.

Certainly these high spirits did not prevent him from being disagreeable with everybody not connected to the film. For example, myself. Each time he caught sight of me he ordered the studio manager to throw me out. This of course could not be done as I had special authorization from the producer to be there. However I was at least made to retreat and hide behind some unused part of the set. Generally Welles only spoke to his direction crew and actors and with his daughter who from time to time came to see him at work.

In spite of giving himself the airs of genius, and in spite of his enormous cigars and his ox-like strength, Orson Welles seemed to me to reveal a side of himself that full of timidity, excessively sensitive and even fearful. The simple presence of a stranger made him nervous. If an actor put forward his point of view, Welles became pensive. In fact I am not at all surprised that he has wanted to work on a film adaptation of The Trial. I believe that Kafka and Welles have many points of contact. They both feel terrified of our modern civilization whose vicious tentacles are taking mankind in their grip. And this impression is confirmed by people who know Welles and have heard him talk at length.

Kevin Hagopian:

Welles had come to know the cul-de-sac world of Joseph K quite well by 1962, when the film, after three years of debilitating deal-making, was finally shooting on the streets of Zagreb, Yugoslavia.After his producers ran short of money, The Trial became another of Welles' "touring productions," a Flying Dutchman of a film whose actors traveled around the world with Welles while he sought financing and locations. After Zagreb, Welles alighted in Paris, where he fumed about the ambitious, studio-shot film The Trial was to have been; now, it was forced, like Joseph K himself, out into the streets. Still awake as dawn broke one morning, Welles noticed a huge, abandoned train station, the Gare D'Orsay. Journalist William Chappell wrote of Welles' inspired inspiration:

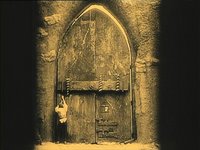

By 7:30 he had explored the lunatic edifice, vast as a cathedral: the great vulgar corpse of a building in a shroud of dust and damp, surrounded and held together by a maze of ruined rooms, stairways and corridors. He had discovered Kafka's world, with the genuine texture of pity and terror on its dark and scabrous walls, real claustrophobia in its mournful rooms; and also intricacies of shape and perspective on a scale that would have taken months and cost fortunes to build.For a man who had once, in more whimsical days, said, "A motion picture studio is the biggest train set a boy ever had," Welles now reenvisioned the shattered old station as the studio his backers had failed to find for him. He found small, cubicle-sized spaces in the station, suitable for intimate moments in Joseph K.'s life, and had these redesigned as bedrooms and offices. In other scenes, the remains of the station's Art Nouveau decor exudes a strange air of the festive gone rancid. His cinematographer, Edmond Richard, used reflected light to capture a dry, flat tone in Joseph's world.

It's customary to imagine Kafka's world as sleek and efficient, its terror arising from its sheer functionality. By shooting in the ancient train station, Welles created another view of the bureaucracy entirely. Here, the regime is a once-glorious structure, gilded and proud, designed to express the grandeur of its motives. Over the years, though, the dreams that were once to be served by the grand engineering symbolized by the train station have grown dusty, even forgotten. The glass is broken, the furniture battered. Mice have chewed the draperies. Now, it is only the machinery that still works, kept well-lubricated as the ornamentation grows rusty and decrepit.

Laughably Obtuse Bosley Crowther NY Times review from 1963:

Whatever Franz Kafka was laboriously attempting to say about the tyranny of modern social systems in his novel, "The Trial" is still thoroughly fuzzy and hard to fathom in the film Orson Welles has finally made from the 40-year-old novel. "The Trial" opened at the Guild and the new R.K.O. 23d Street Theatre yesterday.

Evidently it is something quite horrisic about the brutal, relentless way in which the law as a social institution reaches out and enmeshes men in its complex and calculating clutches until it crushes them to death.

Huw Wheldon 1962 BBC interview with Welles via Wellesnet:

WHELDON: You shot a lot of the film in Paris, at an abandoned railway station, the Gare d'Orsay.

WELLES: Yes, there's a very strange story about that. We shot for two weeks in Paris with the plan of going immediately to Yugoslavia where our sets would be ready. On Saturday evening at 6 o'clock, the news came that the sets not only weren't ready, but the construction on them hadn't even begun. Now, there were no sets, nor were there any studios available to build sets in Paris. It was Saturday and on Monday we we're to be shooting in Zagreb! We had to cancel everything, and apparently to close down the picture. I was living at the Hotel Meurice on the Tuilleries, pacing up and down in my bedroom, looking out of the window. Now I'm not such a fool as to not take the moon very seriously, and I saw the moon from my window, very large, what we call in America a harvest moon. Then, miraculously there were two of them. Two moons, like a sign from heaven! On each of the moons there were numbers and I realized that they were the clock faces of the Gare d'Orsay. I remembered that the Gare d'Orsay was empty, so at 5 in the morning I went downstairs, got in a cab, crossed the city and entered this empty railway station where I discovered the world of Kafka.The offices of the advocate, the law court offices, the corridors-- a kind of Jules Verne modernism that seems to me quite in the taste of Kafka. There it all was, and by 8 in the morning I was able to announce that we could shoot for seven weeks there. If you look at many of the scenes in the movie that were shot there, you will notice that not only is it a very beautiful location, but it is full of sorrow, the kind of sorrow that only accumulates in a railway station where people wait. I know this sounds terribly mystical, but really a railway station is a haunted place. And the story is all about people waiting, waiting, waiting for their papers to be filled. It is full of the hopelessness of the struggle against bureaucracy. Waiting for a paper to be filled is like waiting for a train, and it's also a place of refugees. People were sent to Nazi prisons from there, Algerians were gathered there, so it's a place of great sorrow. Of course, my film has a lot of sorrow too, so the location infused a lot of realism into the film.

WHELDON: Did using the Gare d'Orsay change your conception of the film?WELLES: Yes, I had planned a completely different film that was based on the absence of sets. The production, as I had sketched it, comprised sets that gradually disappeared. The number of realistic elements were to become fewer and fewer and the public would become aware of it, to the point where the scene would be reduced to free space as if everything had dissolved. The gigantic nature of the sets I used is, in part, due to the fact that we used this vast abandoned railway station. It was an immense set.

WHELDON: How do you feel about THE TRIAL? Have you pulled it off?WELLES: You know, this morning when I arrived on the train, I ran into Peter Ustinov and his new film, BILLY BUDD has just opened. I said to him, "how do you feel about your film, do you like it?" He said, "I don't like it, I'm proud of it!" I wish that I had his assurance and his reason for assurance, for I'm sure that is the right spirit in which to reply. I feel an immense gratitude for the opportunity to make it, and I can tell you that during the making of it, not with the cutting, because that's a terrible chore, but with the actual shooting of it, that was the happiest period of my entire life. So say what you like, but THE TRIAL is the best film I have ever made.