Stuart's Nite

CPK Pizzas, Cookies

Special Guest: Lisa Ottotique

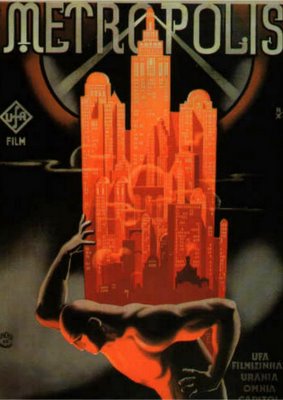

Film Forum: Inspired (or so legend says) by his first glimpse of the Manhattan skyline, Fritz Lang's visionary work of science fiction redefined the term "super-production" - in the process nearly bankrupting Ufa studios - with its thousands of extras (cheap, in the era of Weimar hyperinflation); already-monstrous sets inflated to the gargantuan by cutting-edge camera trickery (including the first use of the legendary Schüfftan process, whereby miniatures and live action are filmed simultaneously); and eye-popping special effects extravaganzas, including the explosion of the "heart machine;" the Frankenstein-like genesis of the robot girl; and a cataclysmic, multitude-engulfing flood.A legend and a byword almost from first release, Metropolis was seen as Lang conceived it only by the earliest Berlin audiences ("positively overwhelming" raved the Variety critic after the premiere) - and then the cutting began, by the U.S. distributor Paramount, by Ufa itself, and so on, down to a 1984 "restoration" that ran only 87 minutes.

Roger Ebert: Generally considered the first great science-fiction film, ``Metropolis'' (1926) fixed for the rest of the century the image of a futuristic city as a hell of scientific progress and human despair. From this film, in various ways, descended not only ``Dark City'' but ``Blade Runner,'' ``The Fifth Element,'' ``Alphaville,'' ``Escape From L.A.,'' ``Gattaca,'' and Batman's Gotham City. The laboratory of its evil genius, Rotwang, created the visual look of mad scientists for decades to come, especially after it was mirrored in ``Bride of Frankenstein'' (1935). And the device of the ``false Maria,'' the robot who looks like a human being, inspired the ``Replicants'' of ``Blade Runner.'' Even Rotwang's artificial hand was given homage in ``Dr. Strangelove.''

What many of these movies have in common is a loner hero who discovers the inner workings of the future society, penetrating the system that would control the population. Even Batman's villains are the descendants of Rotwang, giggling as they pull the levels that will enforce their will. The buried message is powerful: Science and industry will become the weapons of demagogues.

``Metropolis'' employed vast sets, 25,000 extras and astonishing special effects to create two worlds: the great city of Metropolis, with its stadiums, skyscrapers and expressways in the sky, and the subterranean workers' city, where the clock face shows 10 hours to cram another day into the workweek. Lang's film is the summit of German Expressionism, the combination of stylized sets, dramatic camera angles, bold shadows and frankly artificial theatrics.The production itself made even Stanley Kubrick's mania for control look benign. According to Patrick McGilligan's book Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast, the extras were hurled into violent mob scenes, made to stand for hours in cold water and handled more like props than human beings. The heroine was made to jump from high places, and when she was burned at a stake, Lang used real flames. The irony was that Lang's directorial style was not unlike the approach of the villain in his film.

Other dramatic visual sequences: a chase scene in the darkened catacombs, with the real Maria pursued by Rotwang (the beam of his light is like a club to bludgeon her). The image of the Tower of Babel as Maria addresses the workers. Their faces, arrayed in darkness from the top to the bottom of the screen. The doors in Rotwang's house, opening and closing on their own. The lascivious dance of the false Maria, as the workers look on, the screen filled with large, wet, staring eyeballs. The flood of the lower city and the undulating arms of the children flocking to Maria to be saved.Much of what we see in ``Metropolis'' doesn't exist except in visual trickery. The special effects were the work of Eugene Schuefftan, who later worked in Hollywood as the cinematographer of ``Lilith'' and ``The Hustler.'' According to Magill's Survey of Cinema, his photographic system ``allowed people and miniature sets to be combined in a single shot, through the use of mirrors, rather than laboratory work.'' Other effects were created in the camera by cinematographer Karl Freund.

``Metropolis'' does what many great films do, creating a time, place and characters so striking that they become part of our arsenal of images for imagining the world. The ideas of ``Metropolis'' have been so often absorbed into popular culture that its horrific future city is almost a given (when Albert Brooks dared to create an alternative utopian future in 1991 with ``Defending Your Life,'' it seemed wrong, somehow, without Satanic urban hellscapes). Lang filmed for nearly a year, driven by obsession, often cruel to his colleagues, a perfectionist madman, and the result is one of those seminal films without which the others cannot be fully appreciated.

Cinematographer Karl Freund went on to a long Hollywood career, Oscar Bio: Born in Königinhof, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary (now Dvur Kralove, Czech Republic). At the age of 15, Karl Freund began his long, illustrious career in motion pictures as a projectionist. Within two years, he had graduated to camera operator and received a variety of assignments, including newsreels and shorts. In the 1920s, Freund worked at the UFA studios during what has become known as the Golden Age of German cinema. Collaborating with such film artists as Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Paul Wegener and E.A. Dupont, Freund helped to create some of the most beautiful and highly regarded films of the silent era. In 1924, he worked on THE LAST LAUGH with Murnau and screenwriter Carl Mayer. Mayer collaborated closely with Freund to write a script exploiting the potentials of a moving camera. The camera became an integral part of the narrative, interpreting and visualizing the central character's state of mind. To film one scene where the main character is intoxicated, Freund strapped the camera to his chest, batteries to his back for balance, and stumbled about like a drunken man.

In 1925, Freund worked on VARIETY, directed by E.A. Dupont. Once again, Freund's expressive camerawork drew a great deal of praise. Faced with numerous inquiries about the innovative camerawork, Dupont wrote an article for the New York Times explaining the "photographer's ingenuity" in making the film. In 1927, Freund worked with Walter Ruttmann on BERLIN - THE SYMPHONY OF A GREAT CITY. To achieve greater flexibility in difficult shooting situations, Freund developed a special high-speed film stock. The entire documentary was reportedly shot without a single person spotting the camera.

In 1929, Freund came to the United States to work on an experimental color process for Technicolor. Shortly thereafter, he went to work for Universal Studios, shooting DRACULA (1931) and MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE (1932). While under contract at Universal, he directed several films, including THE MUMMY (1932). He went on to work at MGM and Warner Brothers, receiving an Academy Award for his cinematography for THE GOOD EARTH (1937). Freund's work in the United States, including such diverse films as KEY LARGO (1948) and PRIDE AND PREJUDICE (1940), reflected his tremendous range and versatility.

Freund on inventing the techinque of the four camera filmed sitcom for I Love Lucy (Does this sound familar, Pamela?):To film each show we use three BNC Mitchell cameras with T-stop calibrated lenses on dollies. The middle camera usually covers the long shot using 28mm. to 50mm. lenses. The two close-up cameras, 75 to 90 degrees apart from the center camera, are equipped with 3" to 4" lenses, depending on the requirements for coverage.

The only floor lights used are mounted on the bottom of each camera dolly and above each lens. They are controlled by dimmers.

There is a crew of four men to each camera: the cameraman, his assistant, a "grip" and a "cable man." Unlike TV, where one man generally handles the camera movements and views the results immediately, this technique requires absolute coordination between members of the crew.

Every movement of each dolly is marked on the floor for every scene. And since all the movements of the camera are cued from the monitor box, the entire crew works from an intercom system.

As for myself, I utilize a two-circuit intercom. This allows me to talk separately to the monitor booth and the camera crew on one; the electricians handling the dimmers and the switchboard on the other.

Retakes, a standard procedure on the Hollywood scene, are not desirable in making TV films with audience participation. Dubbed-in laughs are artificial and, consequently, used only in emergencies. Close-ups, another routine step in standard film-making, were discarded since such glamour treatment stood out like a sore thumb.

The public acceptance of "I Love Lucy" and "Our Miss Brooks" has been a source of great inspiration for me. The challenge has been a real one -- one I have found both stimulating and exciting.

Danel Griffin: Consider the city itself—an ocean of buildings almost gothic-like in their cathedral shapes, and the airplanes that buzz constantly through the air like small, insignificant bees. Or the underground world of machines that make sure the city runs. This underground workplace is a fortress unto itself, inhabited by faceless, soulless drones who have accepted their fate as the ones who feed the wealthy city above. Some of the first shots that Lang is the back of these men’s heads as they shuffle along to their workplaces, and the image produces goose bumps in its ability to strike us with awe and pity at the same time. Once these images begin, Lang casts a spell on us that is never released, and just when we think that Metropolis has created the ultimate visual achievement, it tops itself with another, and then another (I have two personal favorite images: 1) The clock-like machine in which the protagonist chooses to operate, and 2) the socialist retelling of the story of Babel, with the ocean of bald, moaning heads).

Richard von Busack: Director Fritz Lang makes this an intoxicating mix of dripping romanticism and Biblical fury. It's the cinema's most articulately expressed case of future shock. Metropolis is as pungent as a brilliant editorial cartoon, and it's not dated either. The drones marching into the city's dungeons still chafe the conscience.

Metropolis' repeated motto urges compromise: "Between the mind and the hands, the heart must mediate"--that only common decency can end the war between the haves and the have-nots. This ending was despised by the right and the left alike. Today, it seems insipid--and patronizing too: who decides whether someone's born a "head" or a "hand"?

Fritz Lang Interview:In 1972 my friend, Michael Gould, and I had just graduated from the film program at York University, Toronto, where the school had hosted a number of such luminaries. When we decided to visit Los Angeles together, Michael arranged a number of interviews.

The LA summer was already very hot when we arrived, and Summitridge Drive, high in the Beverly Hills, seemed like a dusty path in some small town on the edge of the Mojave Desert. Fritz Lang's house was small, but it evoked his famous Bauhaus mansion of his UFA days in Weimar, Germany.

Lang welcomed us warmly, smiling and extending both hands, one to each of us, in a gracious gesture full of old-world charm. Surprisingly, considering his reputation on the set, he was a pussycat—soft-spoken, thoughtful and very patient with his two young fans. He served us coffee and delicate cookies from a Viennese pastry shop. Lang had recently undergone a major operation and was recuperating at home. He was tired, but gave freely for several hours, generous with his thoughts and emotions in discussing everything from the art of film to the politics of the '60s.

....

LC: In your work in Germany, you dealt with fantasies and fairytale-like romances, but with M you made an abrupt switch to realism.FL: Not quite correct. I was born in Austria, yes? I became interested in the German human being. I wanted to make a film about the romantic German human being in Destiny; or the German after the First World War, with the Dr. Mabuse films; or the German of legend with Die Nibelungen; or the German of the future with Metropolis. And then I became a tiny bit tired, which had something to do with my private life, about which I don't want to talk.

Michael Gould (MG): In Metropolis when Maria, the robot, dances for the men in formal attire, there seems to be a series of jump cuts. Were these in the original?

FL: Darling, no. There are no jump cuts. I'll tell you what happened. People cut one film, two films, frames. I don't know. When I was in East Berlin they wanted to reconstruct Metropolis and I couldn't help them because I don't have a script. [Note: the current reconstruction retains these cuts.]

MG: Your German pictures were some of the most expensive films made at the time.

FL: There has been written a lot of lies about Metropolis. There were never thousands of extras. Never.

MG: What was the number?

FL: Two hundred and fifty, 300. It depends how you use a crowd. After the first World War there was an inflation, you know? In Die Nibelungen, I think I had 150 knights. The uniforms would have cost a fortune, but when it came to paying it was no more as if we would have paid one knight at the beginning of the film. It was the first time, I think, in history that a country had such inflation.

MG: Were you anxious to begin making sound films?FL: No. When I made Woman in the Moon it was my own company, and the release was UFA. One of the higher echelon from UFA was in the United States and had heard sound on the first Jolson film. He came back and asked me to make sound when the rocket starts. And for me, it was wrong. It was breaking the style of the film. So I said no. And UFA said “If you don't do it, we break our contract; we don't pay you anything!” I said ‘Okay, we'll see.' Then my lawyer said to me “Look, Fritz, you have to deliver everything which you promised.” I didn't get paid for eight or nine months, and UFA hoped that I would finally collapse, but I didn't.

....

FL: I admire all film which is good. But you can learn only from a bad film, not from a good film. I prove it: if you are an audience, you go to a good film. Period. If you see a bad film and you say “What is this? That is wrong. I wouldn't have done it that way,” then you have learned something.

Metropolis Film Archive:

There have been many such assessments over the years which praise the film and recognise its landmark status, or are severely critical and dismissive of it as populist kitsch. Such reviews have become more common with the passage of time. However, just as there were glowing reviews, so also scathing criticisms appeared in the press of the day. The most notorious and vitriolic of these was undoubtedly that published in the New York Times on 17 April 1927 by the well-known English science-fiction writer H.G. Wells. He called Metropolis:...the silliest film. I do not believe it would be possible to make one sillier... That vertical city of the future we know now is, to put it mildly, highly improbable...The hopeless drudge stage of human labour lies behind us. With a sort of malignant stupidity this film contradicts these facts...Then comes the crowning imbecility of the film - the conversion of the likeness of the Robot into Maria...

Thea von Harbou (December 27, 1888 – July 1, 1954) was a German actress and author of some noble Prussian descent.

In 1905, she published her first novel in the Deutsche Roman-Zeitung. However, she then started to work as an actress, starting in 1906 in Düsseldorf, then moving to Weimar (1908), Chemnitz (1911) and Aachen (1913). In Aachen she also met her first husband, the actor and director Rudolf Klein-Rogge, whom she married in 1914.

In 1920, she wrote her first movie script Das indische Grabmal (The Indian Tomb, Mysteries of India), together with Fritz Lang. Fritz Lang became her second husband in 1922, and they collaborated a lot in the following years, for instance in writing the screenplay of the famous film Metropolis together. They separated in October 1931 and got divorced in 1933.

In 1932, one year before Adolf Hitler came to power, she joined the NSDAP. This presumably led to the divorce from husband Fritz Lang who left Germany in 1934 for Paris after his latest film Das Testament des Dr. Marbuse had been declared illegal by Nazi officials because of its criticism of Nazi ideology.Harbou wrote the script for "Der Herrscher" 1937, directed by Veit Harlan and starring Emil Jannings. The movie celebrates unconditional submission under absolute authority, eventually finding reward in total victory.

After the war she was detained by the British military government, and then did some unskilled labor, like cleaning up the rubble from the bombing. After receiving a working permit she did some synchronizing of movies, but also continued to write scripts.

In 1954 She killed herself jumping from a New York City skyscraper.

1 comment:

Following Weblog informs about the scriptwriter Thea von Harbou:

http://medienberatung.blogspot.com

There is also a tillage-possibility for a book about the author.

Post a Comment