Tossed Salad with Roast Chicken, Carrot Cake.

Via AlbertBrooks.com:

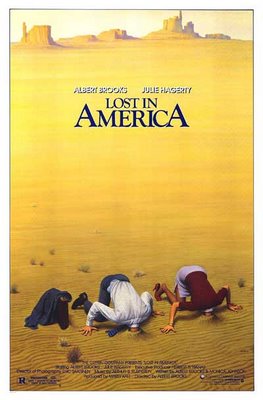

Albert Brooks’ style of comedy is based on the realities of everyday life. On this film, Brooks and his crew spent only three of the film’s 45-day schedule on a sound stage. The rest of the time, they were on location all across the United States.

To provide a vivid, highly American setting for David and Linda’s coast-to-coast odyssey, the filmmakers worked in actual, functioning, facilities, eschewing extras and props in favor of real people and things that were on the scene.

While the filmmakers could have used sound stages to substitute actual locales, producer Marty Katz points out that this compromise “would have cheated the audience of a rich movie experience and wouldn’t have fully expressed the theme of the film.”The story ranges from the work-a-day world of Los Angeles to the razzle-dazzle of Las Vegas to the high energy of New York City; from the stunning beauty of Hoover Dam to the quaint life of roadside trailer camps.

In Las Vegas, the picture company worked and lodged at the Desert Inn Hotel, filming in the casino, lobby, and coffee shop. In the casino, usually seen in films as a distant backdrop, special arrangements were made to enable filming at the gaming tables amid customers and employees.

Armed with the latest lighting advancements of the time and high-speed film, director of photography Eric Saarinen and his crew avoided using the powerful movie lights that would have detracted from the authentic atmosphere of an operational casino.

In striking contrast to Vegas’ neon shimmer was the majesty of the Hoover Dam, where the “Lost in America” company traveled to shoot on both the Arizona and Nevada sides of this landmark.

In New York, David and Linda’s motor home was filmed heading south on Fifth Avenue and pulling to the curb at 57th Street, where David pursues an astonished advertising executive into his office building.

Departing from their New York location, the filmmakers recorded the Howards’ journey from an Arizona trailer camp to wintery Gotham “in reverse” (or opposite direction from their actual travel), necessitating numerous tricky turnarounds.

The trip, depicted in a montage of a few minutes’ screen time, required ten days of grueling roadwork to film. To capture the trek from various points of view, cameras were placed in the motor home’s passenger seat, mounted in a camera car attached to the bizarre convoy, and set up at roadside.

The challenging journey features the deserts of Arizona, the ultra-modern Houston skyline, the Native American atmosphere of El Paso, the Mexican ambiance of Las Cruces, N.M., New Orleans, the Gulf Coast, Atlanta’s Peachtree Plaza, Pennsylvania countryside, and Washington, D.C.’s Capitol.

For the filmmakers, as well as for David and Linda, the journey proved to be an exercise in rediscovering America.

Playboy interview via Unofficial Albert Brooks Page:

PLAYBOY: Do you have muses? Off whom do you bounce ideas?

BROOKS: One of the reasons I married my wife is that she's just got this wonderful brain and a great sense of humor. I talk to her about everything. Also I used to be really close, like talking daily, to Jim Brooks, who gave me those roles in Broadcast News and I'll Do Anything. When I wasn't in As Good As It Gets, I stopped talking to him. Better put me in the movies, Jim, if you want to be my friend.But, over the years, I've actually written all but one of my movies with Monica Johnson, who's the sister of the comedy writer Jerry Belson. She sort of found me through Penny Marshall and I thought she had great comedic sensibilities. She innately understands the Albert Brooks "character" in these films. And she's a woman which is always a good thing when you write. She makes me laugh. And she's a great laugher, too. I could never write with someone who didn't laugh well.

PLAYBOY: Is laughter better than sex?

BROOKS: Gee, I always thought it was the same thing.

PLAYBOY: Describe the upside of becoming a father in your fifties.

BROOKS: Having a child when you're a little bit older—I'm not talking Tony Randall older—is the coolest thing in the world. The concerns you have when you're thirty about your own career and stuff are huge. But there's just something great about getting past that period so you can really devote your attention to someone and mean it. I don't know what else there is to do on earth. I guess the downside, however, is we're already looking at high schools with wheelchair ramps.

PLAYBOY: So, anyway, how well did you perform in the delivery room?

BROOKS: I cried. When the head popped out, I just wept.

PLAYBOY: You gave up singlehood during maybe the randiest presidency in the history. Did you have any favorite passages from the Starr report?

BROOKS: I have to say this: My child is not old enough where I'm getting a lot of questions. But I think it might be uncomfortable if you have a kid around 5 years old. The president should not be responsible for the word head coming up at dinner. That should come from the father. When I'm ready to tell my kid what head is, I'll tell him. I don't want the president telling him. "Daddy, what is being on your knees in the Oval Office?" "Well, that's a kind of Moslem prayer. . ."

PLAYBOY: Did your parents know you were funny?

BROOKS: I don't recall that my mother ever thought I was funny. That's why I wrote Mother, which is what the whole movie was about. I know she's very proud of me and I can make her laugh today. But, for most of my life, it didn't matter how funny I was or how funny anybody told her I was—she was very serious about me having another business to fall back on. But I still wanted her approval. I would call her after every Carson appearance—"What did you think?" And she would always, always have the same answer: "Oh, it was wonderful! What did Johnny think?"

And I'd say, "Well, you saw the show--did you hear the audience laughing?"

"No, no, I just wondered . . ."

"What—did Johnny secretly hate me even though they were laughing? No, he likes me!"

So, one day, I actually planned this whole strategy. I'd been waiting for this moment—I did the show, the audience was laughing its head off, and, as ever, she said, "What did Johnny think?" And I sounded very depressed: "I don't want to talk about it. Things are not good."

"What happened?"

"Well, Johnny came into the dressing room and he said 'You'll be the last Jew to ever appear on my show!'"

"What?!?"

Now, of course, my mother was immediately furious: "Don't ever do that show again! If he's anti-Semitic--"

I said, "I'm just kidding."

PLAYBOY: Real Life was released in 1979 and now, twenty years later, your sixth film is finished. What takes you so long?

BROOKS: Well, there would have been more if I could have gotten the financing money easier. Out of those twenty years, there was a good eight spent raising the money! I knew that as soon as I put the words The End on a script, I was going to have to go through these mine fields that I just hate more than the world. Even for this movie. The Muse was written right after Mother—which means it could have been finished and released over a year ago. Paramount passed, so it took longer. It's just very hard to go through the humiliating experience of 20 people saying no till one person says yes.

PLAYBOY: How humiliating has it gotten?BROOKS: Lost in America was maybe the worst—I went for two years trying to raise money. I wouldn't wish it on anybody, because 99% of these potential investors just want to meet people in show business. You go out to dinner with them and you still pick up the check. You meet these big fat guys from Texas and they're listening to the idea—"So then they go to Vegas and she loses the money—" And the Texas guy interrupts: "Yeeeahh, um, Allll-buht, do you know any hookers?" I learned, by the way, to start out every meeting by saying, "Hello, I don't know any hookers. Now let me pitch you this story."

PLAYBOY: Your films have had completely original comic premises. Can we inventory the inspirations for each? Already, for instance, Real Life has been echoed by The Truman Show and EdTV. You got there first.

BROOKS: Echoed!? Jon Bon Jovi's endtitle song for EdTV was called "Real Life." I mean, come on! When Monica Johnson heard that, she called me in tears. But I suppose it's actually a good thing—maybe it reminded people. Real Life didn't make any money, but at least The Truman Show got some Oscar nominations out of the subject. The important thing is that Real Life still holds up.

PLAYBOY: How about Lost in America?

BROOKS: I always loved the idea of making a life-long decision and finding out four days later that it was wrong. You know, burning your bridges and then having to eat shit. Here was this successful married couple who sell their house, buy a Winnebago, hit the road, lose everything in a week, and realize they've made a mistake. So the concept was all about backing up and eating shit. We all do it in little ways. I wanted to see it big.

Glenn Erikson via DVDSavant:

Lost in America's lesson is that modern urban society makes us status-conscious, artificial, and shallow, but that there are lots of worse things to be and worse situations to find oneself in. When David's back in his element again, slugging away with his cheerfully obnoxious business persona, it's obvious that's where he belongs, and at least now he knows it. Albert Brooks doesn't insist that you see his comedies as 'meaningful,' and they're certainly just as hilarious without any of this thinking ... but it puts him far ahead of the game, up there with the classic comedies.

Most of the setpieces in the film are inspired, and a couple are simply transcendant. Probably the best is David's pitiful attempt to talk a casino executive (Garry Marshall) into giving back the money they've lost at his roulette wheel. David's sorry belief that his ad-man patter can coax money from this man is funny, almost painfully so.Julie Hagerty makes an excellent foil for Brooks, as undemonstrative and thoughtful as he is brash and exaggerated. She makes Linda Howard the kind of person who's genuinely surprised by her own susceptability to the gambling bug, and yet we know she isn't damaged by her husband's tirade of sarcasm when her 'little mistake' turns into disaster. In most of Brooks' stories he doesn't link up well with females, the ending of Defending Your Life being the only slightly strained part of that film. David and Linda are a good couple. Woody Allen basically believes relationships are impossible, and even his sweetest movies reflect this cynicism. Neil Simon conceives of characters as collections of kooky quirks, and all any Simon relationship needs to succeed is for people to to get past one another's idiosyncrasies. All three write funny movies, but I like Brooks' philosophy the best. It actually takes into account the idea that we can be smart enough to understand at least part of our own contradictory natures. Even if we can't change everything about our lives, we can be happier by improving our attitudes.