Nora's Nite

Nora's NitePasta with SuperDelicious Meat Sauce with mushrooms, onions and tomatoes, Cookies, Ice Cream

Jonathan Kiefer on George Roy Hill: There's a great story about how George Roy Hill used to spook fatuous Hollywood studio executives by buzzing their office tower with his antique open-cockpit biplane. He would come in low, blending with the skyline at first, then, with a crescendo of engine roar and a beeline swoop, plunge straight at the conference-room windows, turning sharply up and away just in the nick of time -- or, to really push the envelope, just a split second after the nick of time. The executives might not necessarily accede to Hill's creative demands from then on, but they would possibly wet themselves.

The story implies a spirited, bravely black-humored, possibly dangerous, but ultimately appealing lone adventurer (read: a George Roy Hill protagonist). It was told by Stephen Geller, who wrote the screen adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five for Hill to direct, and it sounds like a tall tale -- Geller is a peerless raconteur -- until you consider the recorded manifestations of Hill's personality.Take, for instance, what is widely viewed as Hill's most cherished film project, The Great Waldo Pepper (1975), with Robert Redford as a flying stuntman who tends to articulate his more dramatic sentiments aerially. Or the great, ridiculous scene in Hill's movie of John Irving's The World According to Garp (1982), in which a sputtering small plane emerges from the nether-regions of suburbia to crash into the protagonist's first house just as he's about to buy it. "We'll take the house," Garp cheerfully replies. "It's been pre-disastered!"

Perhaps it goes without saying that this scene is not in the book, but it should be mentioned that the pilot in the movie is Hill himself, who, after wrecking the house, politely asks if everyone is all right and then asks to use the telephone. The moment seems to expose the director's creative attitude toward life in this world, and it's a relief to say that even after September 11, it's still very moving and funny.George Roy Hill died recently, just after his 81st birthday, from complications of Parkinson's disease. Low-flier that he was, his passing evaded a few radar screens, but his contribution is worth remembering.

Born in Minneapolis, Hill studied music at Yale, then served as a Marine transport pilot in the South Pacific during World War II. The G.I. Bill allowed him to further his studies of music and literature at Trinity College in Dublin, where he began acting, with Cyril Cusack's company at the Abbey Theatre. There, Hill promptly made a successful move into directing, and then brought that success to Broadway. After more military service during the Korean War, he began writing, producing, and directing for American television during its mid-fifties golden age. His first theatrical feature film was an adaptation of Tennessee Williams' Period of Adjustment, which Hill had directed on Broadway.

Hill didn't start making films until the age of 40, and he stopped at 66, with 14 singular, award-winning, and influential works to his credit. He is most famous for originating the screen team of Paul Newman and Robert Redford, without which, it is safe to say, American cinema would be significantly blander. The team only convened for two films, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1973), but their mark on future generations of on-screen con men, lovable bandits, and other basically good bad guys is indelible. (There is also the matter of Redford's moviemaking sub-empire, gratefully named for the role that made him a star.)Some of his flights of fancy, perhaps predictably, crashed and burned. But the majority of Hill's films are smartly entertaining and richly quirky. For a while, he was the only director in history to have made two of the top 10 moneymakers (the Redford-Newman films), a real feat for someone who, rather unlike the cookie-cutter moviemakers enjoying similar -- and useless -- accolades now, did such truly personal work and still made it popular. Bear in mind that Hill, during his television days, was responsible for A Night to Remember, the original Titanic movie, and the first version of Judgment at Nuremberg, the original Holocaust confrontation movie.

What the cinema will really miss, though, is his charisma, his voice. What Roger Ebert wrote of Funny Farm, the last, is true of many George Roy Hill pictures: the director "enlists our sympathies with the characters even while cheerfully exploiting their faults." Hill did make his characters suffer -- dramatically and comically. It wasn't schadenfreude, but rather something close to the opposite, a tough and tender kind of empathy, and the resolve to laugh, hard, at affliction.

For all the delight he took in vindicating the heady schemers of The Sting, Hill seemed to feel most deeply for the humiliations suffered by Garp, or the passive, put-upon Billy Pilgrim of Vonnegut's novel. Butch and Sundance were ultimately doomed, themselves "pre-disastered," but that fact never impeded their symbiotic sense of humor.William Goldman, who wrote Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and won an Oscar for it, finds the movie especially vindicating, and Vonnegut and Geller are both rightly proud of Slaughterhouse Five. That too is a major feat for any film director who dares adapt any book. John Irving was less pleased, but one look at his sodden The Cider House Rules suggests he should count his blessings.

Because you must go somewhere after the funny farm, Hill returned to teach at Yale. He didn't talk to the press much (he never had), so he was periodically characterized as a "recluse." A lone adventurer, perhaps, but not a recluse. At least his colleagues didn't seem to see him that way. But perhaps they were ducking under their desks.

TIME on Slaughterhouse-Five: Vonnegut is still more cult favorite than literary lion (and he probably prefers it that way), but he deserves full canonical marks for this kaleidoscopic koan of a novel about Billy Pilgrim, a man who has "become unstuck in time." Pilgrim ricochets helplessly from decade to decade, living the episodes of his life in no particular sequence, not excluding his own death, his capture by aliens called Tralfamadorians, and his traumatic service in World War II, when he lives through the firebombing of Dresden. Slaughterhouse-Five is a cynical novel, but beneath the bitter, grim-jawed humor is a desperate, painfully honest attempt to confront the monstrous crimes of the 20th century.

NY Times Reviews Slaughterhouse-Five via Vonnegutweb: Kurt Vonnegut Jr., an indescribable writer whose seven previous books are like nothing else on earth, was accorded the dubious pleasure of witnessing a 20th-century apocalypse. During World War II, at the age of 23, he was captured by the Germans and imprisoned beneath the city of Dresden, ''the Florence of the Elbe.'' He was there on Feb. 13, 1945, when the Allies firebombed Dresden in a massive air attack that killed 130,000 people and destroyed a landmark of no military significance.

Next to being born, getting married and having children, it is probably the most important thing that ever happened to him. And, as he writes in the introduction to Slaughterhouse-Five, he's been trying to write a book about Dresden ever since. Now, at last, he's finished the ''famous Dresden book.''

In the same introduction, which should be read aloud to children, cadets and basic trainees, Mr. Vonnegut pronounces his book a failure ''because there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre.'' He's wrong and he knows it.

Kurt Vonnegut knows all the tricks of the writing game. So he has not even tried to describe the bombing. Instead he has written around it in a highly imaginative, often funny, nearly psychedelic story. The story is sandwiched between an autobiographical introduction and epilogue.

Via Vonnegutweb.com: Writing in Critique, Wayne D. McGinnis comments that in Slaughterhouse Five, Vonnegut 'avoids framing his story in linear narration, choosing a circular structure.

Such a view of the art of the novel has much to do with the protagonist . . . Billy Pilgrim, an optometrist who provides corrective lenses for Earthlings. For Pilgrim, who learns of a new view of life as he becomes ''unstuck in time,'' the lenses are corrective metaphorically as well as physically. Quite early in the exploration of Billy's life the reader learns that ''frames are where the money is.'' . . . Historical events like the bombing of Dresden are usually 'read' in the framework of moral and historical interpretation.' McGinnis feels that the novel's cyclical nature is inextricably bound up with the themes of 'time, death, and renewal,' and goes on to say that 'the most important function of "so it goes" [a phrase that recurs at each death in the book] . . . , is its imparting a cyclical quality to the novel, both in form and content. Paradoxically, the expression of fatalism serves as a source of renewal, a situation typical of Vonnegut's works,for it enables the novel to go on despite -- even because of -- the proliferation of deaths.'''

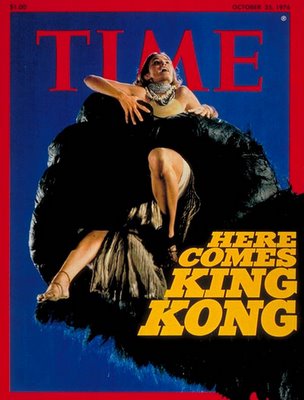

Superficial Valarie Perrine bio: This brash, statuesque former Las Vegas showgirl brought a blowzy sultriness and a sweet vulnerability to a number of starring and supporting roles in the 1970s and 80s.

The daughter of a US Army officer and a former Broadway dancer, Valerie Perrine was raised in various places around the world, including Japan. After briefly studying psychology, she began her show business career as a topless dancer in Las Vegas. Perrine traveled throughout Europe and lived for a time in Paris before finally settling in L.A. in the early 70s. Landing her first role as Montana Wildhack in George Roy Hill's screen adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut Jr.'s "Slaughterhouse-Five" (1972), she was singled out for her portrayal of a voluptuous kidnapped bride of the hero (Michael Sacks).This led to her first starring role as the trampy girlfriend of race car driver Jeff Bridges in "The Last American Hero/Hard Driver" (1973). Perrine had what was perhaps her best role to date as Honey Harlowe, the drug-addicted stripper-wife of comic Lenny Bruce in Bob Fosse's biopic "Lenny" (1974). Bringing class and smarts to what could have been a stereotypical role, she proved to critics and audiences just how strong an actor she could be, given the right material. Perrine earned awards from critics groups, won an Oscar nomination as Best Actress and received the Best Actress trophy at the 1975 Cannes Film Festival.

Screenwriter Stephen Geller is now Associate Professor of Film at BU:

BA, Dartmouth College; MFA, Yale University. Professor Geller has taught film and the creative process at Dartmouth College, in the MFA Creative Writing Program at Arizona State University, and has lectured on cinema throughout the world. An internationally recognized screenwriter, Professor Geller has worked for nearly 30 years in the American, French, Italian, and British film industries. His screenplay for Slaughterhouse-Five won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival, as well as a nomination by the Writer's Guild of America. His miniseries, Warburg: A Man of Influence, won the coveted European Silver Award for Best Miniseries. Most recently, with his writer-wife Kae, he wrote and performed in the play Opportunities in Zero Gravity in Boston and New York and, also with his wife, won the Zoetrope International Internet Film Festival for their short film, Cuppa Cabby, Piece O' Pie, which played in national and international film festivals. He has published four novels, a book on screenwriting, and has written extensively for diverse publications.

Geller recently made his own low budget film:

Geller first had to raise money and recruit a cast and crew, then survive on four hours' sleep a night as he juggled filmmaking with summer classes, a wife and five-year-old daughter, and a cast that included nearly a dozen young, partying actors. Why not just write the script and shop it around Hollywood? Because, he answers, he has been disappointed too many times to let others interpret his work. “I've been paid to write forty-two films,” he says, “and nine have been made, and I have never been satisfied with the direction of a majority of them, except for George Roy Hill's direction of Slaughterhouse-Five. The rest of the time I found that I was brighter than most directors, actually knew more about film, and cared more about film. And so this time, I knew I was going to make this movie.”The film was shot in twenty-nine days, cost $125,000, and “everybody who was involved owns a piece of it,” Geller says. Almost all the cast and crew were BU faculty and students, which helped make the balancing act work. Geller's wife, Kae, a film lecturer at COM, played a major role, and their daughter, Florrie, was junior production assistant. “He'd written one of the most extraordinary parts ever written for a woman,” says Kae, who has cowritten and starred in several projects. “It was an amazing experience to be a part of it.” Colleague Kevin Bliss (COM'96), also a COM film lecturer, took a role in the film even before reading a final draft of the script. “I know Steve,” he says, “and I knew I'd feel good about whatever he writes.”

Geller's more than thirty years in the film industry have earned him a reputation primarily for screenwriting. Among his credits are the adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.'s Slaugherhouse-Five, for which he won a Special Jury Award at the Cannes Film Festival and a Writers Guild nomination for Best Screen Adaptation, and Warburg: A Man of Influence, a miniseries that won the European Silver Medal Award for Best Miniseries of 1992.

“I had had nine contracts to direct something I had written,” he says, “but for a variety of reasons they never came through. Either I walked away because it didn't contain the elements I wanted, or the producer found me unbearable, or we lost the money.”

Why might a producer find him unbearable? “Because I know what I want,” Geller says. “And my experience with producers and directors is that they don't know what they want.” He likens shooting a movie to “watching water boil. I love the writing, I love the rehearsals, I love the cutting. The shooting itself is an absolute bore.”

Bombing of Dresden:Contemporary official German records give a number of 21,271 registered burials, including 6,865 who were cremated on the Altmarkt.[26] There were around 25,000 officially buried dead by March 22, 1945, war related or not, according to official German report Tagesbefehl (Order of the Day) no. 47 ("TB47"). There was no registration of burials between May and September 1945.[27] War-related dead found in later years, from October 1945 to September 1957, are given as 1,557; from May 1945 until 1966, 1,858 bodies were recovered. None were found during the period 1990-1994, even though there was a lot of construction and excavation during that period. The number of people registered with the authorities as missing was 35,000; around 10,000 of those were later found to be alive.[28] In recent years, the estimates have become a little higher in Germany and lower in Britain; earlier it was the opposite.

Overall, Anglo-American bombing of German cities claimed around 400,000 civilian lives. Whether these attacks hastened the end of the war is a controversial question. As acts of retaliation, they were at best vicarious (even if entire nations are seen as morally competent agents).